Eleven, Eleven, Eleven — I

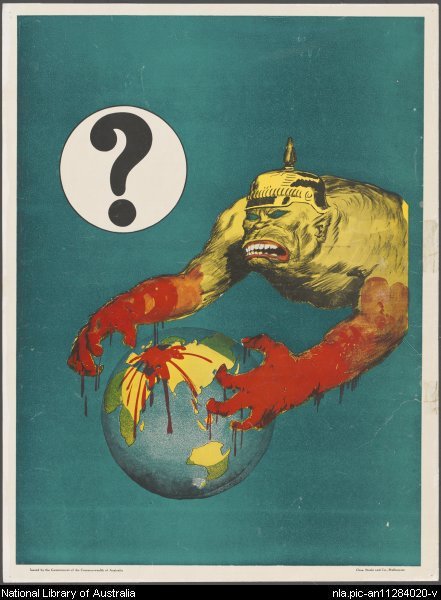

This summary of an unreleased and untitled film is from the ‘Grave and Gay’ column of the Preston Herald for 7 December 1918: In this film a man dreams that England is under German rule, and various scenes are shown depicting the organised brutality of the Boche. But, in the dream, there is a movement […]