The fourth RAF Pageant took place on Saturday, 30 June 1923. The ‘turn of the afternoon’, as in the previous year, was ‘another little Eastern drama, based on actual happenings during the War’.1 Once more the Wottnotts were the enemy, and once more the co-operation of air and ground forces was the theme. The main difference with 1922 was that this time the RAF was coming to the aid of a besieged garrison:

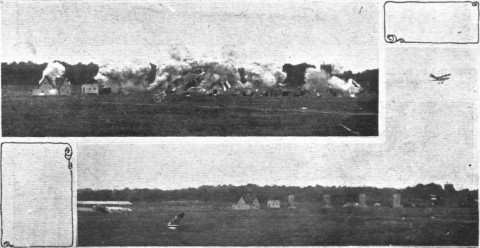

On the centre of the “stage” one saw an impressive railway bridge and sundry buildings. The small military garrison protecting this post was suddenly attacked by our old friends (or enemies?), the Wottnott Arabs. The garrison, being outnumbered, W.T.’d for help, which, before you could say “Jack Robinson,” appeared in the form of three Vickers troop carriers, escorted by five Sopwith “Snipes.”2

But something had to be be blown up, and so the troop carriers are used ferry troops who destroy a bridge and thereby save the day.

The troop carriers landed beside the bridge, small parties of machine gunners emerging from their interiors and rushing to the assistance of the garrison. In the meanwhile the “Snipes” hold back the Wottnott Arabs with machine-gun fire, whilst the garrison emplanes in the troop carriers, and a demolition party charges under the bridge for the purpose of its utter destruction. When all was ready, the guard blew his whistle, and the troop carriers sailed away for safety. Then the bridge blew up, which so annoyed the Wottnotts that, after all falling down dead, they got up and made a dash, to the accompaniment of wild yells, for the public enclosures.

What remained of the spectators after the horrible slaughter then witness the final event of the day [the usual smokescreen-laying].3

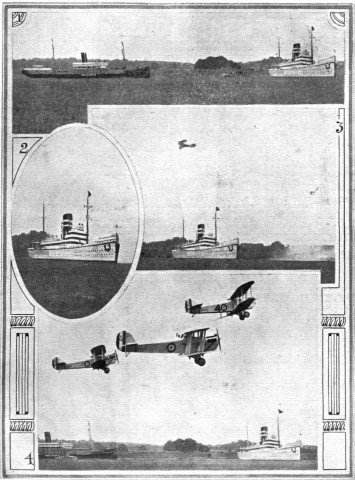

There was a change of scenery in the final for the next year’s Pageant, held on Saturday, 30 28 June 1924.4 Spectators were invited to make believe that the grass at Hendon represented the sea, upon which were two enormous ‘ships’, essentially flat stage props cunningly painted to give the illusion of three dimensions (at least from where the spectators were standing):

One was ‘an English cargo ship, the “John Henry” of Newcastle, and the other a peaceful-looking, but armed enemy merchant cruiser, the “Slevic”.’5 The scenario here was that the Slevic ordered the John Henry to stop and prepare to be boarded. Luckily, a RAF Supermarine Seagull appeared on the scene and radioed for help. This came in two waves. The first consisted of three Fairey Flycatcher ‘ship’s fighters’, which strafed the Slevic and put its guns out of action.6

Then the second wave arrived:

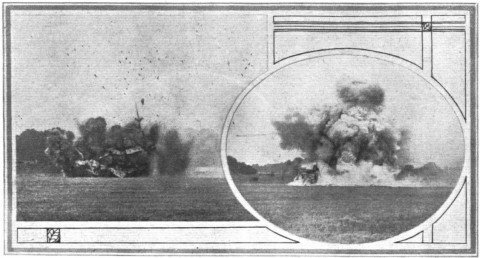

Suddenly, five Blackburn “Dart” torpedo ‘planes arrived on the scene, and making for the “Slevic” launched their torpedos. The latter were observed to fall one after the other and travel a short distance towards their object before finally disappearing from view in the grass (sorry! sea!!). Then a few awful moments passed, when, suddenly, with a loud boom a column of smoke and “water” shot high up into the air at the “Slevic’s” bows, exposing to view, immediately after, a huge ragged hole in her bows. Almost at the same time the other torpedoes found the mark, one right amidships. There was a terrific explosion, a mass of dense black smoke mixed with flying fragments of “Slevic” following by a column of what appeared to be a mixture of smoke and steam. Gradually this cleared away — and the “Slevic” had completely disappeared!2

Thus concluded what in Flight‘s opinion ‘was, undoubtedly, the best scenic display the Pageant has yet given — equal to any other we have seen’.2 British Pathe liked the sinking of the Slevic too, choosing it to open their newsreel coverage.

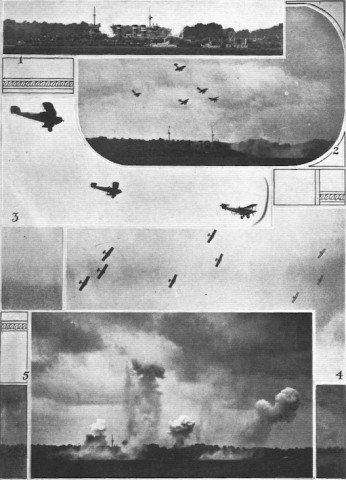

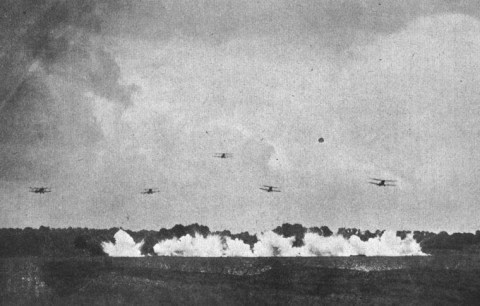

So successful was it, in fact, that the finale to the next Hendon — held on Saturday, 27 June 1925, and now renamed the RAF Display — was very similar. The commerce raider this time was found sheltering in a tropical river rather than sailing on the open sea, so the RAF didn’t send in torpedo bombers. Instead, the Seagull and the Flycatchers reprised their 1924 roles, and then:

After a short interval a fleet of heavy bombers, consisting of three Avro “Aldershots,” and nine Vickers “Virginias,” arrived on the scene from a base conveniently situated close at hand, and with few Oh very direct hits put an end to the cruiser’s nasty bad habits.7

If there’s a theme to these set pieces, it’s substitution: i.e. the substitution of airpower for military power and seapower. Anything the Army and Navy can do, the RAF can do better. It can patrol the Empire’s reaches more efficiently and more effectively, bringing greater force to bear more quickly than can even tanks and battlecruisers. (Indeed, another Hendon standby at this stage was the bombing and destruction of a tank.) Certainly, as Major F. A. de V. Robertson noted, ‘The public probably never stopped to inquire how nine “Virginias” and three “Aldershots” [based in Britain] arrived off the coast of Africa, or wherever it was’.8 But that’s precisely why the Hendon spectaculars made such powerful propaganda for the RAF.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

The Wottnots seem suspiciously well-organised and equipped. Is it okay to blame Iran yet?

It’s also interesting that the set-piece ends with the garrison withdrawing from its fortress, and even blowing up the railway bridge it was supposed to protect. Imperial retreat?

Interesting that they had an airmobile/airborne theme as early as 1923. That would have to be one of the very earliest airmobile operations, even just as a display. Also, how airminded is it to be all about close air support and tactical transport?

Another thought – the troops who landed to carry out the air assault. Were they RAF personnel or Army? The RAF Regiment didn’t exist then.

As far as the mission itself goes, it seems to be a mixture of an airmobile QRF going out to reinforce the outpost, a commando raid to destroy a high value target, and a combat-SAR mission to recover people on the ground. A threefer!

Per Wikipedia, Billy Mitchell and Lewis Brereton were thinking about inserting troops behind the front by air during planning for the Allied 1919 offensive, but they didn’t get as far as doing anything concrete before the Armistice. The Italians are credited with the first actual drop of paratroopers in November 1927.

Erik:

It might be dangerous to read too much into the specific details of each year’s set-piece: there were non-strategic imperatives too, such as the need to entertain, the need to come up with new variations. And apparently the need to make do with bits of old aeroplanes and hangars for construction material! Anyway, I’m sure every yeoman of the Empire knew in his sturdy heart that sometimes setbacks took place and you might have to blow up your own bridge. The important thing was the RAF saved the day in the end.

Alex:

Yes, it’s interesting, isn’t it. Some British airmen were certainly thinking of things like this during the war: e.g. in 1917 PRC Groves suggested airlanding roughly division-sized units operationally (e.g. to take out enemy artillery before launching a ground offensive) or strategically (e.g. to destroy factories). As you say it didn’t happen, but it is tempting to look at this as a step on the road to the knock-out blow.

About the identity of the troops in this scenario: presumably Army. In the Iraq mandate, the RAF had overall command of all British forces so Army units were at its disposal. (It also had its own armoured car squadrons, precursors of the RAF Regiment, but I doubt you’d want to separate them from their vehicles!) I do find it odd that Flight‘s commentary says the set-piece was based on actual events from WWI; as you say nothing like this happened then, it’s close to contemporary operations in Iraq (though even using a great deal of imagination).

a little contribute:

during 1918, the III° Italian Army III sent four officers in espionage missions behind enemy lines. The mission was organized in collaboration with British intelligence, in particular with Lieutenant Ben Wedgwood. The British provided the parachutes (mod. Calthrop) and the pilot, the Canadian W. Barker. The four spies were the Lieutenant of Alpini Barnaba Pier Arrigo, Lieutenant Alexander Tandura, Lieutenant Ferruccio Nicoloso, and Lieutenant Antonio Pavan

The aircraft was a twin-engine reconnaissance Savoia Pomilio S.P2 modified with a folding seat by means of a lever that was operated by the pilot or observer, placed at the bow of the aircraft. The parachutist was therefore forced to travel with his feet dangling in the air and with his back turned to the direction of flight, waiting for his seat was overturned and he began to fall. The parachute, housed in a case placed under the fuselage and connected by means of a rope to the belt of the paratrooper, he would be open because of the traction. This seems to be the first infiltration by parachute behind enemy lines.

seems that the French Vedrines, Evrard, Tabuteau, and the Germans Windisch von Kossel performing similar missions, but I have not found data on these …

Pingback: Airminded · Ending Hendon — III: 1926-1928

Thanks; I’ve discussed Wedgwood Benn before, but I certainly didn’t know the details! There’s also this on a possible German attempt to do the same thing.

Pingback: Airminded · Ending Hendon — V: 1932-1934

Pingback: Airminded · Comparing Hendon

Pingback: Miroirs de la ville #12 Une histoire du bombardement « Urbain, trop urbain