Don’t waste coal and other exhortations!

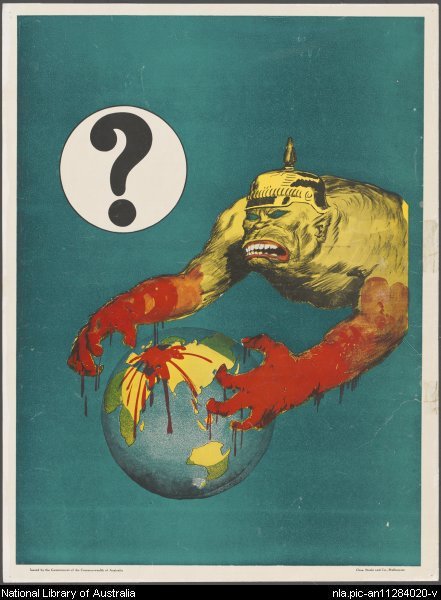

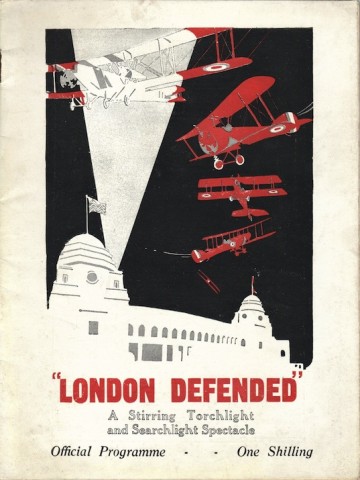

This image and the one below are selections from the The National Archives’ collaboration with Wikimedia Commons, so far comprising 350 examples of war art from the Second World War. These particular ones are propaganda posters (or draft versions of same) but there are also more informational ones as well as portraits and caricatures of […]