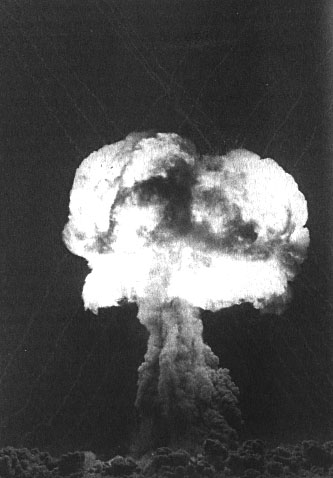

The last time Britain nuked Australia

The last time Britain nuked Australia was at Maralinga on 9 October 1957, over half a century ago. The last of the Antler series of tests, code-named Taranaki (above), involved the detonation of a 25 kiloton fission bomb from a captive balloon at a height of 300 metres. The fallout ‘moved east and then north-east […]