Signs of the times

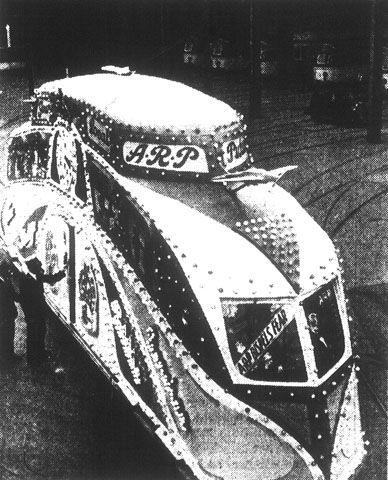

An illuminated tram-car which is touring Blackpool as a recruiting agent for the A.R.P. services.1 Every autumn in Blackpool, the promenade is festooned with miles of multicoloured lights — the ‘Blackpool Illuminations‘. Part of this display involves similarly-decorated trams — the ‘Blackpool illuminated trams‘. (Or so I read, I’ve obviously never been.) This particular example […]