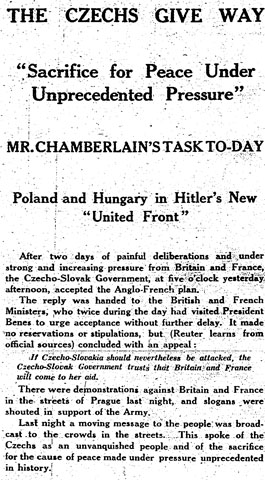

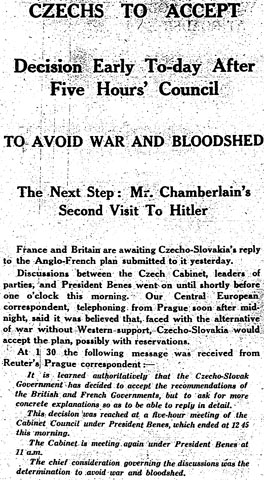

Thursday, 22 September 1938

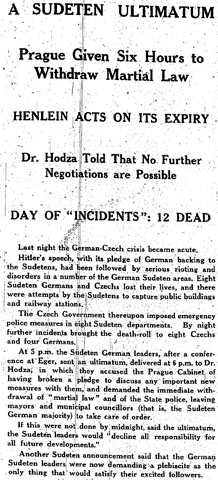

Chamberlain is meeting Hitler at Godesberg today (the headlines are from the Manchester Guardian, p. 11). The good news (for Chamberlain, anyway) is that the Czechoslovakian government has finally, and very reluctantly, accepted the Anglo-French plan for the transfer of German-majority areas to Germany. (Which, it seems, still hasn’t been officially published.) That would mean […]