Self-archive: ‘The shadow of the airliner’

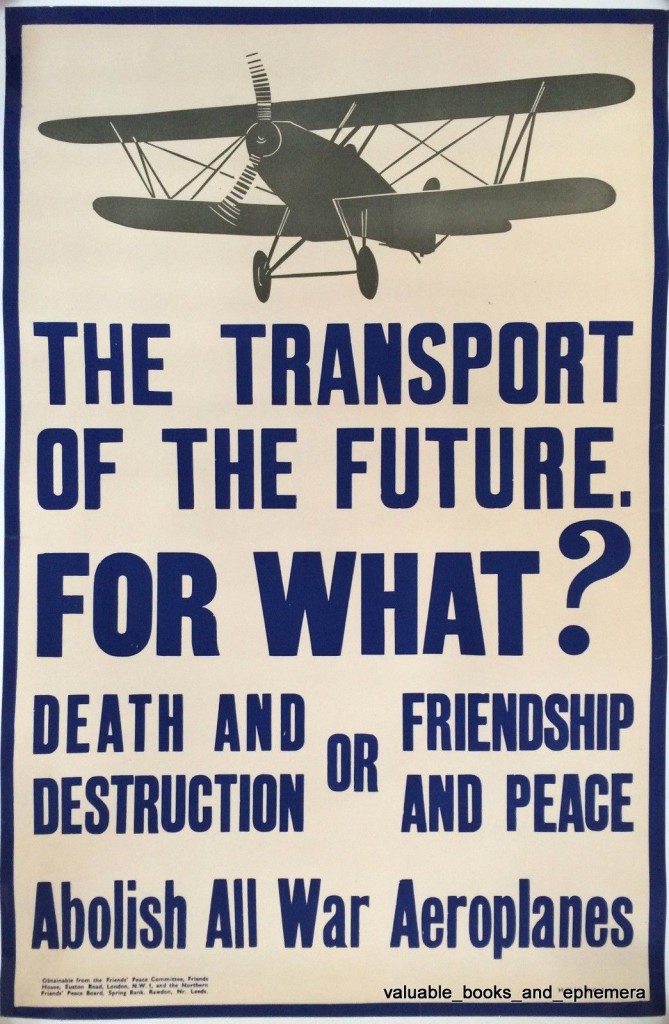

A few years back I published an article, ‘The shadow of the airliner: commercial bombers and the rhetorical destruction of Britain, 1917-1935’, in Twentieth Century British History. At that time I was given a link for free downloads which I provided for those without instiutional access. But it turns out that (1) I wasn’t really […]