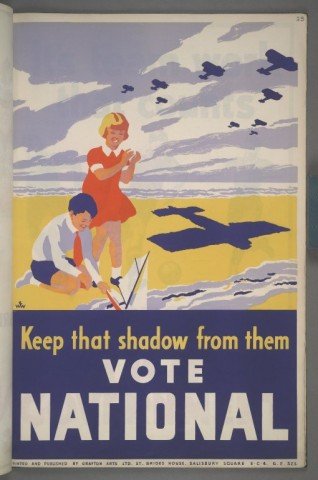

Black death rain

In a discussion of the activities of MI5’s Port Control section during the First World War, Christopher Andrew mentions German musings about using biological weapons against British civilians: The most novel as well as the most sinister form of wartime sabotage attempted by Sektion P was biological warfare. At least one of its scientists in […]