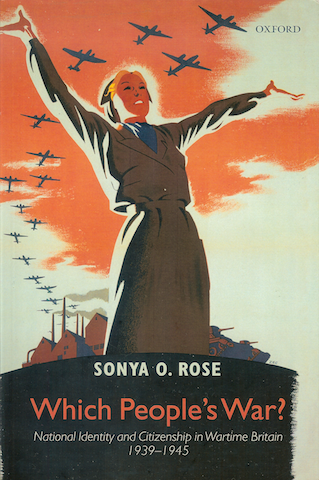

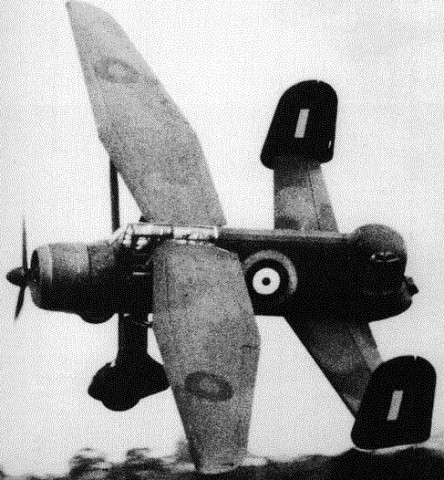

Odd plane out

I recently read Sonya O. Rose’s Which People’s War? National Identity and Citizenship in Wartime Britain, 1939-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), which is interesting on such subjects as anti-Semitism during the Blitz. But I kept being drawn back to the front cover, for a completely trivial reason. The illustration is from a 1941 poster […]