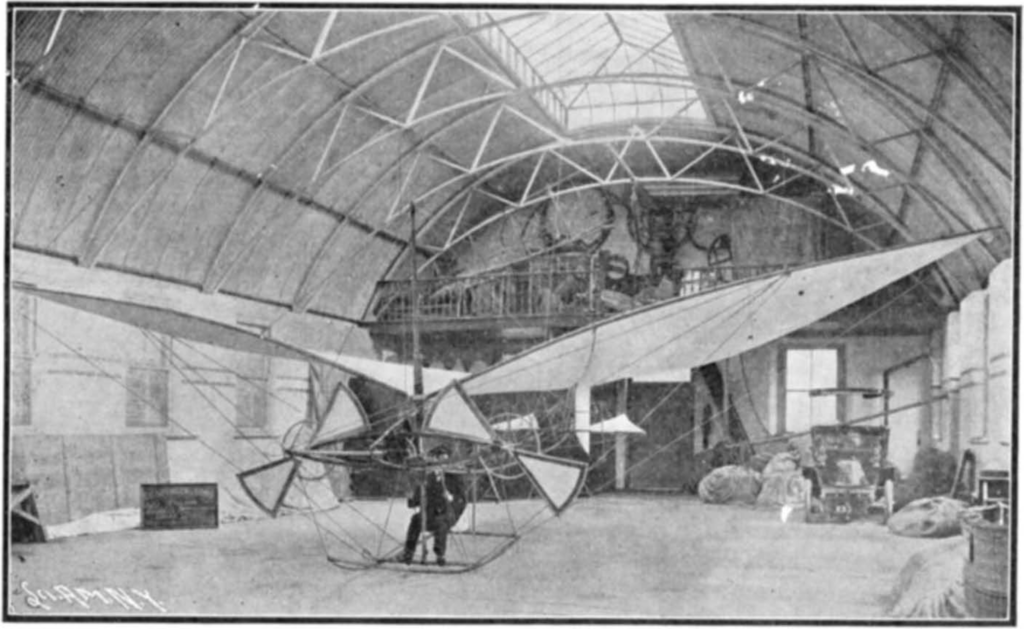

The mysterious flying machine of the mysterious Señor Alvares — II

Here is what I’ve been able to reconstruct about the Alvares flying machine. Firstly, nothing about Alvares himself, except that he was a Brazilian, who was said to have successfully carried out experiments with smaller gliders in his home country for some 18 years.((Manchester Evening News, 17 September 1904, 3; Daily Mirror (London), 17 September […]