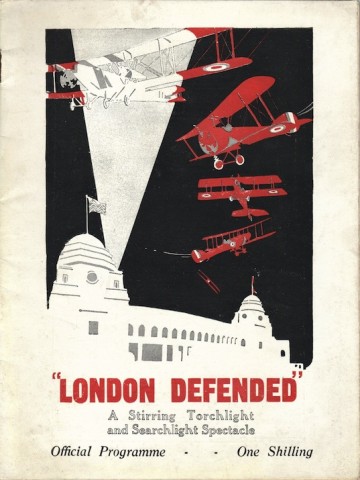

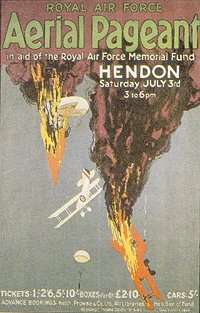

Ending Hendon — VI: 1935-1937

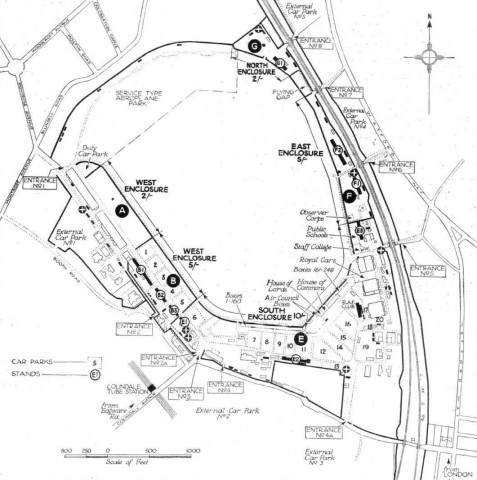

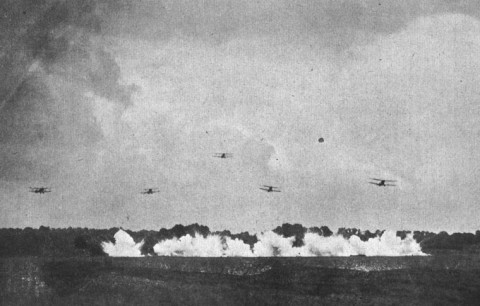

My main interest in this series about the RAF Displays at Hendon has been in the set pieces with which they ended. But as this is the last post it’s worth looking a bit at the organisation of the Display itself. Flight had some useful articles for this in its preview of the 15th Display, […]