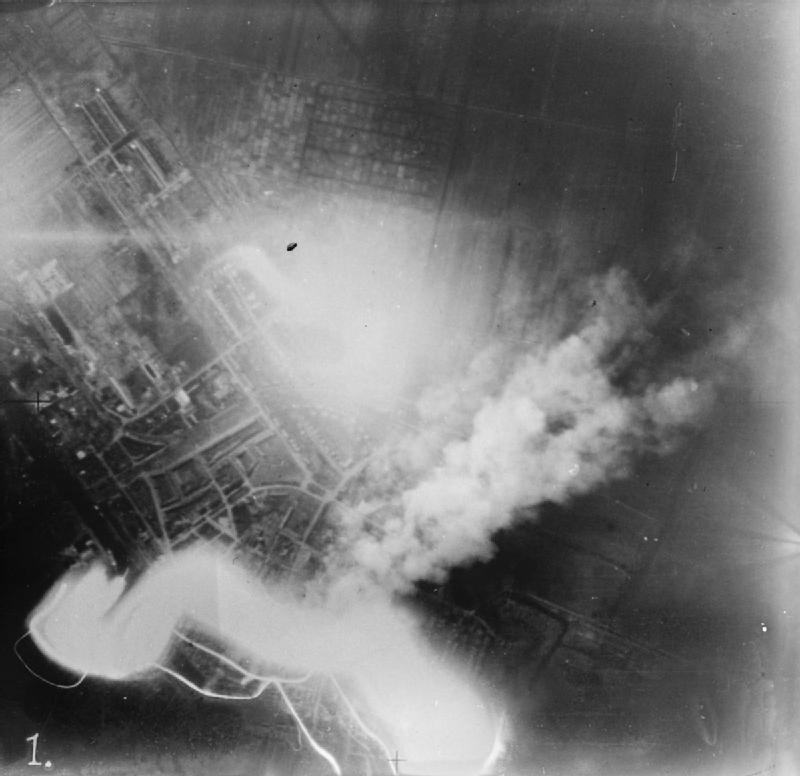

The first blockbuster

One factlet I’ve enjoyed dropping on the heads of students is the origin of the word ‘blockbuster’. Now it is widely understood to mean a hugely successful movie (as well as a once-highly successful video rental chain — remember those?). It has even been claimed that this is the original sense of the word: supposedly, […]