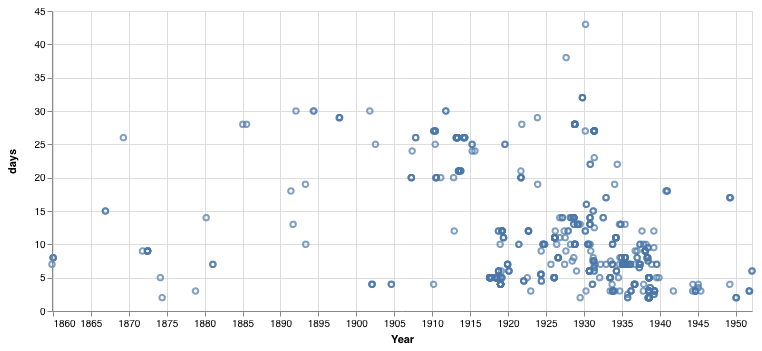

It’s that quote again — I

The man: Stanley Baldwin. The place: the House of Commons. The date: 10 November 1932. The quote: I think it is well also for the man in the street to realize that there is no power on earth that can protect him from being bombed, whatever people may tell him. The bomber will always get […]