Peace

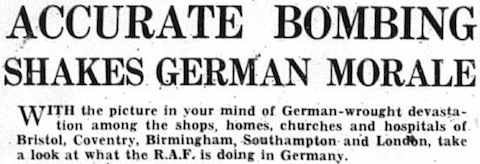

This was one of several colour images of wartime London published by the Daily Mail (for which see a much bigger version; but do not read the comments). I have nothing interesting to say about it; I just like it, is all. (Via @lucyinglis and @fleming77.)