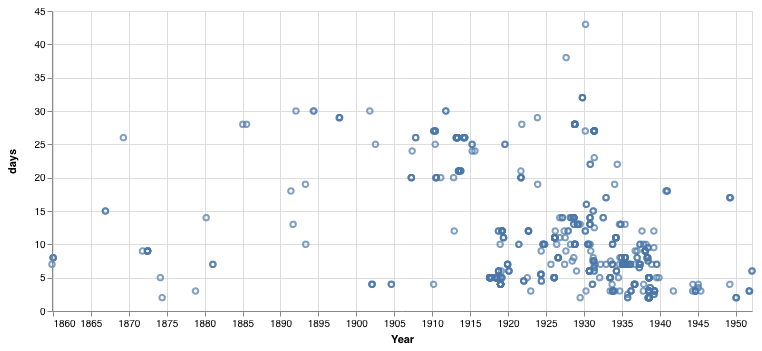

It’s that quote again — II

Stanley Baldwin’s ‘the bomber will always get through’ speech was not widely quoted in the British press in the 1930s. But when it was quoted, how was it used? To determine this, I’m going to do a closer read through of the British Newspaper Archive (BNA).