Return to call of the clouds

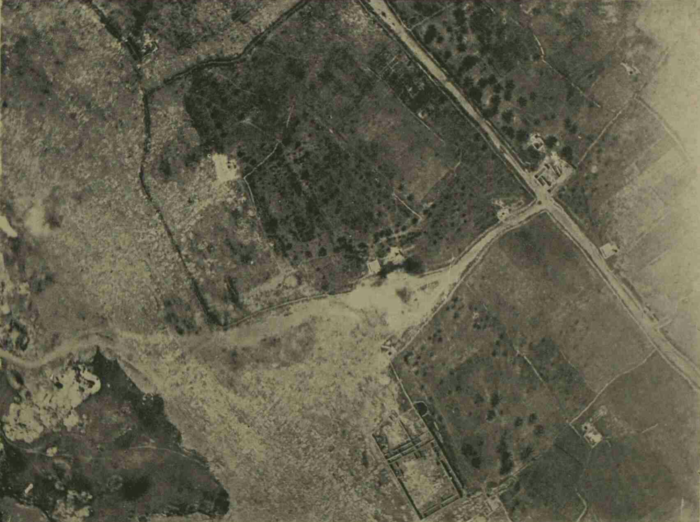

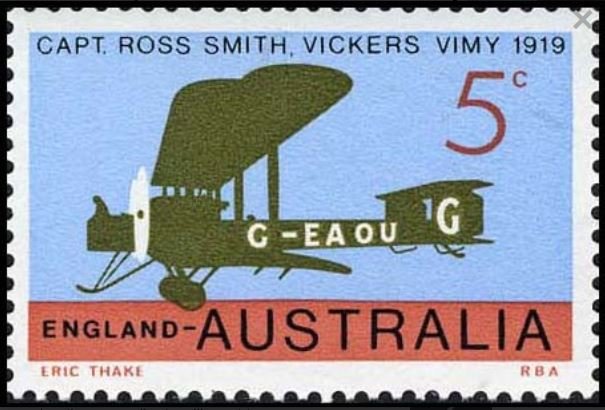

Last year I looked at a couple of fantastic photographs from the State Library of South Australia’s collection, taken at Harry Butler’s ‘Aviation Day’ display at Unley on 23 August 1919. They’re fantastic because they focus not on the flying but on the crowds watching it. Now I’ve found two more photos taken on the […]