Lady Drogheda’s Great Air Exhibition — I

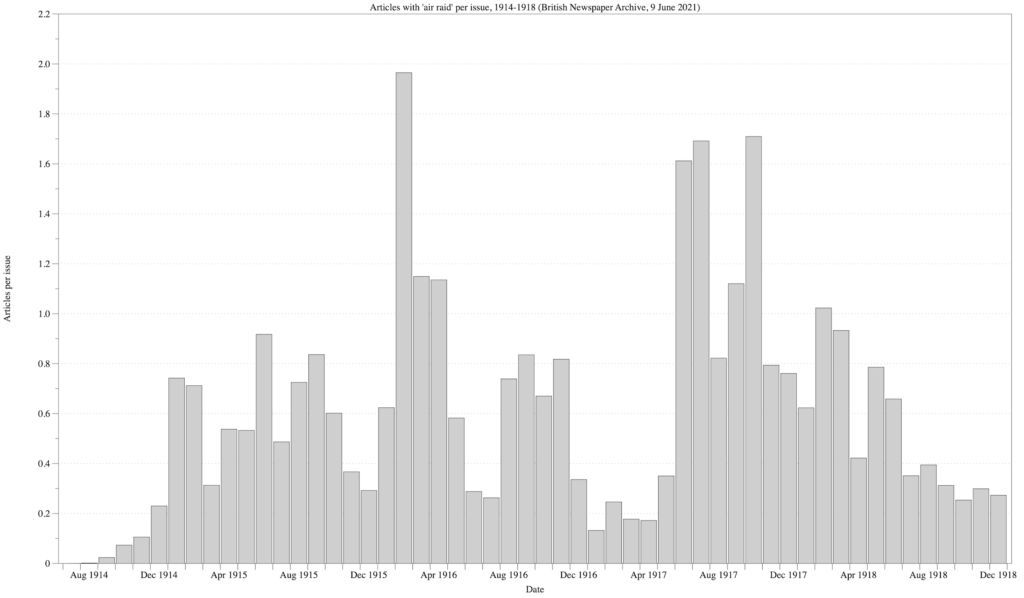

This advertisement, which appeared in the East Ham and South Essex Mail on 2 November 1917, excited my curiosity. An exhibition of German aircraft… held in the East End of London… just after the Harvest Moon raids? I’m there! Or would be if time travel was a thing. As it’s not (yet…) I’ll have to […]