Self-archive: ‘William Le Queux, the Zeppelin menace and the Invisible Hand’

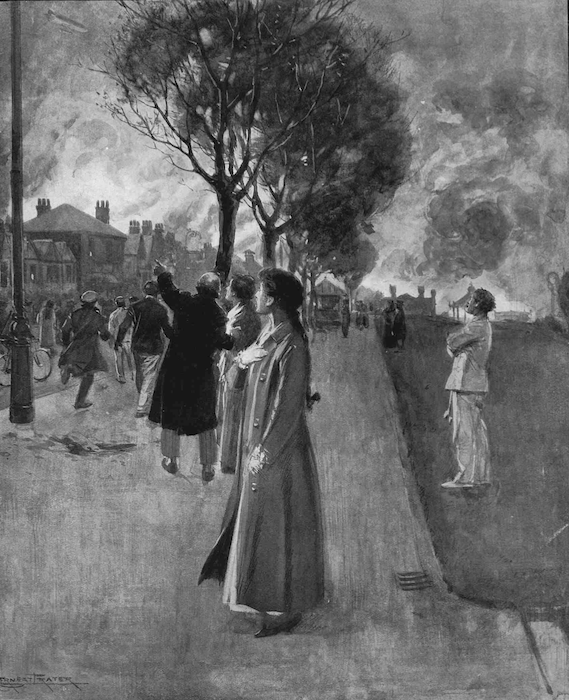

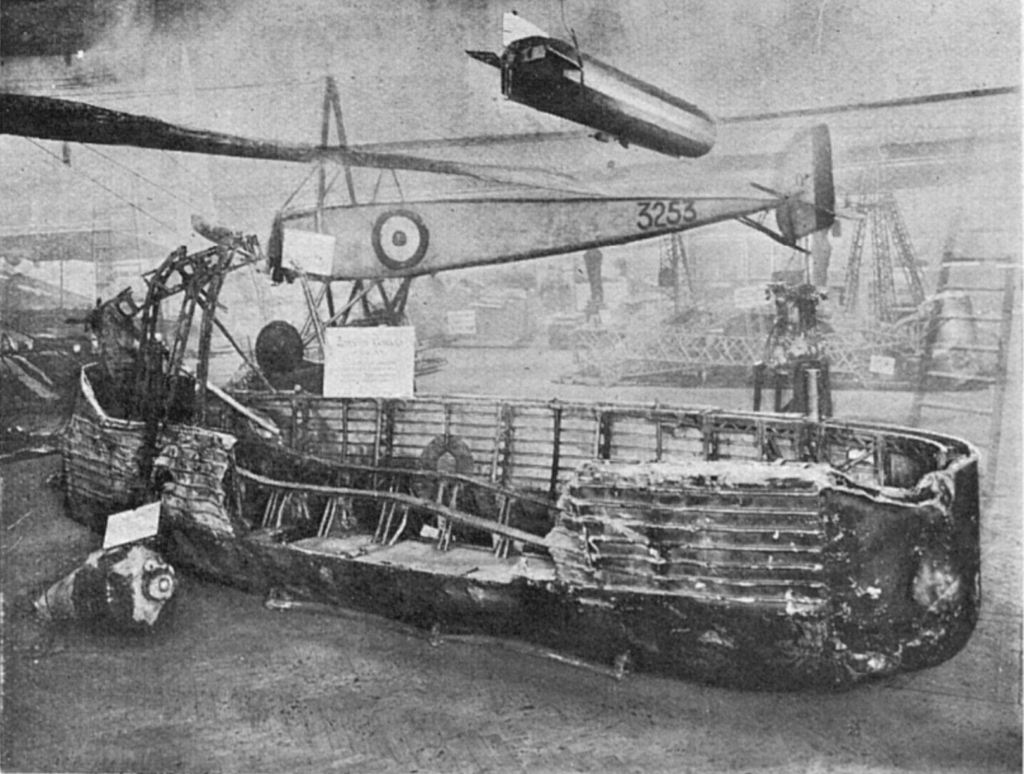

A few years back, my article ‘William Le Queux, the Zeppelin menace and the Invisible Hand’ was published in Critical Survey, with the following abstract: In contrast to William Le Queux’s pre-1914 novels about German spies and invasion, his wartime writing is much less well known. Analysis of a number of his works, predominantly non-fictional, […]