From conference to conference

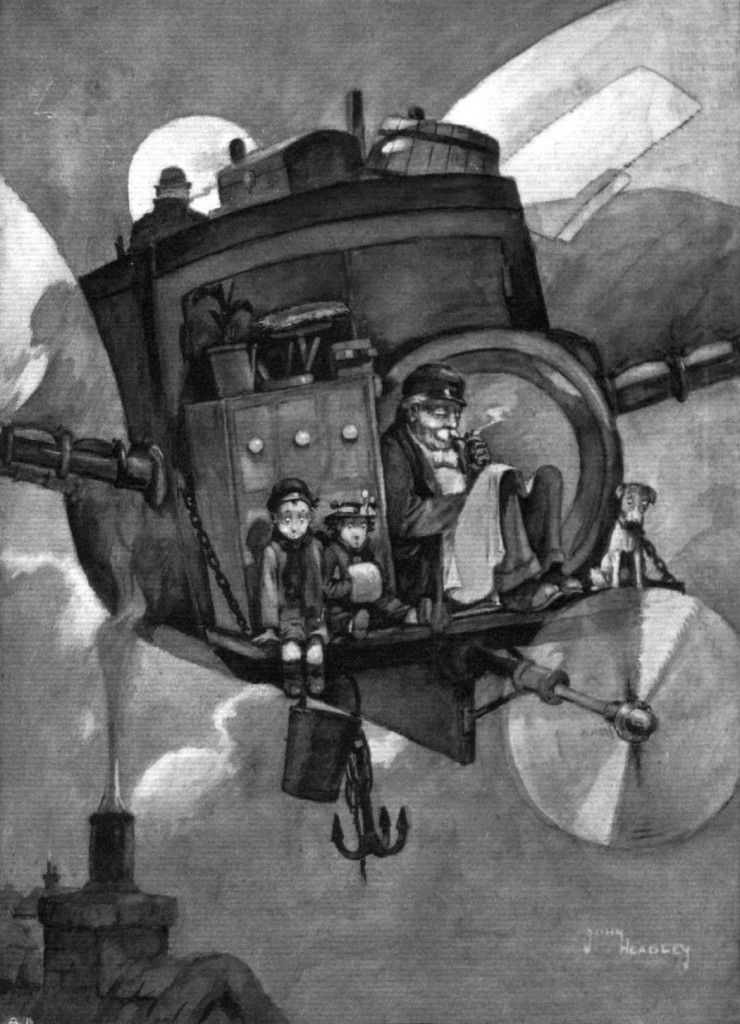

No sooner is one conference over than another one looms. The one which is over is the Australian Historical Association annual conference for 2014, which was held last week at the beautiful St Lucia campus of the University of Queensland. I spoke on the topic of invasion, Zeppelin and spy scares in Britain during the […]