In between conferencing and researching, I managed to fit in some sightseeing in Wellington. It really was only a day or two, and sometimes the weather was somewhat inclement, but I did see some of the main attractions. Above is a detail of the portico of the beautiful Wellington Railway Station, which opened in 1937. I must admit to only using it for the conveniently-located supermarket inside.

The first sight that I saw was the sea. Wellington is blessed with a beautiful harbour (not shown: the beauty) surrounded by hills. The city centre runs along the waterside, so salt water is only ever a few minutes' walk away.

The port is a very active one, with freighters and other vessels coming and going all the time. Though most are more salubrious than this, the Southern Prospector, a trawler which has apparently been laid up here for years.

So it was appropriate that my first museum was the Museum of Wellington City & Sea, which is about Wellington's maritime history as well as its social and cultural history (the artefactual timeline of the twentieth century worked really well for me). It's located in the Bond Store, which used to house the Wellington Harbour Board. The rather opulent board room has been preserved; in one of the anterooms is a memorial to their employees who fell in the First World War. The museum also has displays relating to the history of New Zealand's maritime defences, which included mention, I was pleased to see, of the Kaskowiski affair (even though that didn't happen in Auckland, not Wellington).

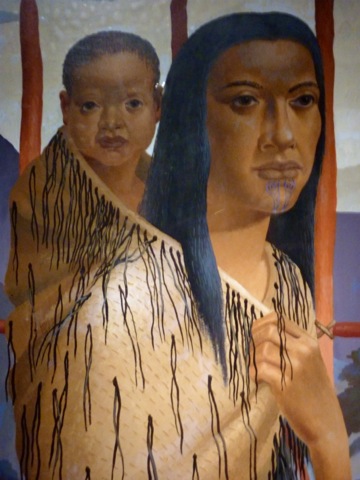

There was a permanent exhibition to the Wahine disaster. Wahine was a ferry linking the North and South Islands on the Wellington-Lyttelton route. On 10 May 1968 it encountered the worst storm in New Zealand's history -- the collision of an extratropical cyclone and an Antarctic storm -- as it entered Wellington Harbour. After struggling towards safety for hours, it eventually foundered, and out of the 733 people on board, 53 perished. Taking place so close to Wellington, the disaster and attendant rescue efforts were a media sensation which left behind dramatic images and some artefacts -- such as this mural by James Turkington, Wahine (which is the Māori word for 'woman'). Water damage can still be seen at the top.

There were no extratropical cyclones in sight on my next trip to the waterfront. The ship is the Hikitia, a floating steam crane built at Glasgow in 1926. Behind it is the national museum, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the national museum, usually just known as Te Papa. Spoken by about 4% of the population, Māori is one of New Zealand's official languages, though in terms of signage and official documents it doesn't seem to be as bilingual as Wales, say.

Te Papa Tongarewa is Māori for 'container of treasures'. Taumata atua means 'resting place of a god', which is what this stone is. It would have been placed among the crops, so that the god could come to protect them and ensure a good harvest.

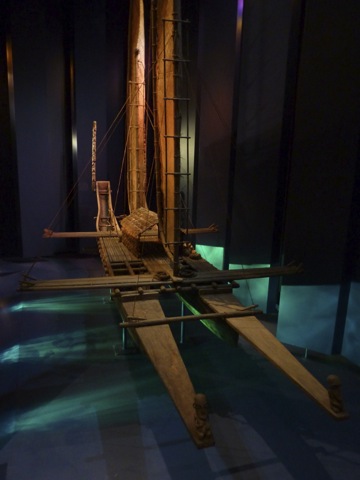

Canoes, or waka, were very important in pre-contact Māori culture, not only for the obvious practical reasons of transport and fishing, but because tradition and mythology recalled their use in the migration to New Zealand. They might have looked something like the above, a scale replica of a modern ocean-going canoe built in the Cook Islands, which has sailed all over the Pacific.

A figurehead from the prow of a canoe which was buried in wetlands some time in the three centuries before Europeans arrived. According to the exhibit caption this was done both for preservation and as an offering to Papatūānuku, the earth goddess.

Yet another canoe, I'm afraid. This time it's a waka taua, a war canoe, belonging to the Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi people. It is named Teremoe and fought in several battles in the 1860s, between Māori and Māori and Māori and Pākehā.

Pākehā is the Māori term for New Zealanders of European descent (though use of the term is contested; not all Pākehā would accept the label). Relations between the two groups have not always been friendly. Arguably this is where the conflict started, the so-called Harriet affair. In 1834 the Harriet ran aground off the Taranaki coast, carrying settlers back from Sydney. The survivors were attacked by two different iwi; some of the male captives were released in order to come back with a ransom of gunpowder. Instead they brought back HMS Alligator and a detachment of Redcoats. Eventually the last of the Harriet's survivors were freed; the watercolour above shows the rescue of John Guard, aged 3, the first Pākehā born on the South Island. According to the Sydney Herald,

[F]inding the child safe, [the crew of the Harriet] now determined to take full revenge for the murder of their shipmates, and there being about 103 natives on the beach, we fired on them; and the soldiers on the hill supposing that orders had been given for firing commenced a discharge of musketry upon them.

The incident was notorious enough to be condemned by a parliamentary committee back in London, but the watercolour, 'The rescue of John Guard, then a child of three years of age by Captain Lambert of HMS Alligator', was painted half a century later, suggesting that it was remembered differently by European New Zealanders.

This cannon has significance for both New Zealanders and Australians. It was cast overboard from HMS Endeavour in June 1770, in a (successful) attempt to lighten the ship after running aground on the Great Barrier Reef. The significance of this is that Endeavour was James Cook's ship, and on this voyage it was used to chart both New Zealand and the eastern coast of Australia for the first time. In 1969, the cannon was recovered along with five others which are now dispersed around the world.

(A model of) HMS New Zealand, a battlecruiser commissioned in 1912. It was a gift from New Zealand to the mother country, promised during the dreadnought panic in 1909 to alleviate the cost of the naval arms race with Germany. Australia also did its part by funding a sister ship to New Zealand, but HMAS Australia, as the prefix suggests, remained in Australian hands (in adherence to the abortive 'Fleet Unit' concept of imperial defence). New Zealand fought in most of the actions in the North Sea, including Jutland where the lead ship of its class, HMS Indefatigable, was sunk after a magazine explosion. New Zealand came through more or less unharmed; Australia missed the battle completely thanks to a collision with none other than New Zealand. Lest we forget...

This friendly fellow is well-known to New Zealanders and Australians alike, though maybe not so much in this form. He is of course Phar Lap, a champion racehorse who won 37 times in 51 starts, including a Melbourne Cup, between 1929 and 1932. The legend goes that his victories buoyed morale during the Great Depression, with correspondingly greater anguish when he died mysteriously after winning the Agua Caliente in Mexico; it's certainly true that he has been long remembered in both countries (like many a Kiwi, he emigrated to Australia for career reasons). I've now been in the presence of two of the three Phar Lap relics: his skeleton in Wellington and his hide in Melbourne; only his heart in Canberra remains to be seen.

Your common or garden Tiger Moth. The significance of this one is its use by James Aviation as an aerial topdresser between 1949 and 1956. Aerial topdressing is the use of aircraft to spread fertilisers on crops (cf. crop dusting, the aerial delivery of pesticides). New Zealand pioneered the development of aerial topdressing in the late 1930s and 1940s. Why New Zealand? The Wikipedia article on aerial topdressing notes a number of factors: a supportive public service, the rugged nature of much of New Zealand's farmland, high prices for their major products (lamb and wool), and the postwar availability of ex-RNZAF aircraft and aircrew.

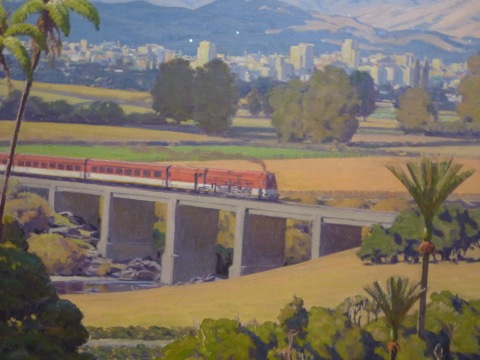

A detail from a painting by Marcus King, dating to 1950-5. A green and pleasant land, with trains.

This twisted piece of copper used to be part of a ship called Rainbow Warrior. On 10 July 1985, French agents attached two limpet mines to Rainbow Warrior while it was moored in Auckland harbour and detonated them, sinking the ship and killing one of the crew. The reason why France carried out such an unfriendly act in an unfriendly nation was because Rainbow Warrior was Greenpeace's flagship, and was due to lead a flotilla to Muroroa to protest the French nuclear tests there. Unfortunately for France, two of their agents were captured by New Zealand authorities, and after initial denials the French government was forced to admit responsibility. Not a proud moment in French history.

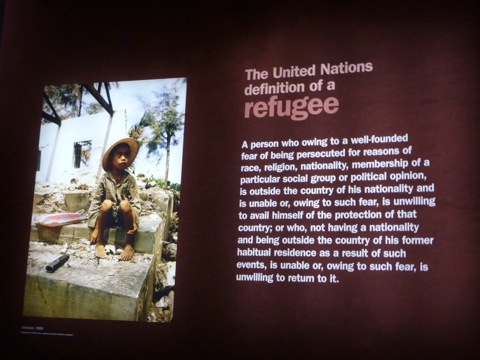

The United Nations definition of a refugee:

A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

As an Australian, I was quite literally ashamed to walk through this exhibit about the welcome given to refugees in New Zealand. And that was before Australian policy became even harsher. I probably couldn't even face it now.

On my last morning in Wellington, I braved gale-force winds to take in a few more of the city's sights. This one I'd actually seen before, though, since the conference had been held inside it. Depending on the source, and whether you believe in number agreement, the Old Government Buildings either is or was or are or is the second-largest wooden building world and the largest in the southern hemisphere. Also, supposedly the first ever building with a smoke-free policy -- not for public health but due to the fire risk. Eventually the public service outgrew it, and it's now the Law School of the Victoria University of Wellington.

The Executive Wing of the New Zealand Parliament Buildings, less formally known as the Beehive. This is where Cabinet meets and the various ministers have their offices (Parliament proper is in the stone building on the right. The statue is of Richard Seddon, prime minister 1893-1906). In the basement is a civil defence command bunker which can theoretically withstand an earthquake of more than magnitude 8, so the magnitude 6.5 one which hit Wellington a week after I left would barely have had an effect (on the bunker, that is).

Next to the Beehive is the Wellington Citizens' War Memorial (not to be confused with the National War Memorial which is in Mount Cook, not to be confused with Aoraki/Mount Cook), dedicated thirteen years after the First World War and re-dedicated seven years after the Second.

On the front side, a relief shows a soldier leaving his family to go to war.

Maybe somebody can explain this to me. The aircraft chosen to represent the Royal New Zealand Air Force on the cenotaph look like a Hurricane and a York. But as far as I can tell, the RNZAF never flew Yorks and only had a handful of Hurricanes (unless you count Article XV squadrons in the RAF). Better choices would have been a Dakota and a Kittyhawk or Mustang, surely.

The Wellington Cable Car runs from the CBD up to the Botanic Garden. It's been running since 1902, when it was an actual cable car, rather than a funicular as it is now. Apparently there are a hundred or so private funiculars in Wellington, thanks to all the hills, but this is the only one I saw.

The view is much better on a sunny day -- I've seen photos!

Also in the Botanic Garden is this extremely rare Krupp 13.5cm field gun, overlooking the city and the sea. Less than two hundred were ever built and this may be the only one left. It was captured by the New Zealand Division at the Canal du Nord on 29 September 1918 and in 1920 came to New Zealand as a war trophy. A gun battery had in fact been located here in the late 19th century with a 7-inch disappearing gun, and a rangefinder where the little dome is.

Little domes often lead to bigger domes. The little one in the previous photo housed an astrolabe during the International Geophysical Year; the biggest one is the Carter Observatory, once New Zealand's main research observatory. Given that the middle of a city is not exactly ideal for astronomical observations, that function is now performed by Mount John University Observatory, with Carter focusing on a public education role. It's been refurbished in recent year and now sports a whizzbang new planetarium. (Which I didn't visit because the next show was aimed at 7-year olds.)

Carter's pride is a 9¾-inch Cooke refractor. It was built in 1866-7 in York for an English amateur, then brought to New Zealand in 1907 for a presumably rich clergyman, purchased by Wellington City Council in 1924 and ended up at Carter when it was opened in 1941.

I was intrigued by Carter's library. Much of it was donated by Leslie Comrie, a New Zealander who fought on the Western Front and later graduated with a PhD in astronomy from Cambridge. Comrie was a pioneer in the field of computational astronomy, which then relied upon mechanical calculators rather than electronic computers. He formed the first scientific computing company, Scientific Computing Service, Limited, in 1937 and during the war did things like devise bombing tables for the fabled Norden bombsight. In 1941, Comrie, who was then in London, sent fourteen cases of astronomical books and journals, some quite rare, to Carter. Anecdotal evidence suggests that he did this because he was worried that civilisation in Europe, or at least in Britain, would be destroyed, and so he wanted to make sure that the astronomical knowledge built up over the centuries would be preserved in far-off New Zealand. If that's true, his choice of books is quite interesting. In the above photo can be seen Percival Lowell's three classics: Mars (1895), Mars and its Canals (1906), and Mars as the Abode of Life (1908). As I've discussed, professional interest in the canals lingered long after the hypothesis was supposedly demolished in 1909; and perhaps these books represent a youthful interest in the controversy on the part of Comrie. (Though many of his books were acquired from the estates of other astronomers.) But what are we to make of the presence of Ignatius Donnelly's Atlantis (1882), H. P. Blavatsky's Collected Writings (1883), J. W. Dunne's An Experiment with Time (1927) and The New Immortality (1938)? Clearly not all of the books in the above photo were donated by Comry: K. R. Lang's Astrophysical Formulae was a standard text when I was an astrophysics postgrad, which wasn't that long ago. Some of the other esoteric titles fall into this category: William Corliss' Mysterious Universe, Jacques Vallee's Anatomy of a Phenomenon and The UFO Enigma, and Immanuel Velikovksy's Earth in Upheaval were all published after Comrie's death in 1950. So perhaps they reflect Carter's acquisition policy: but even allowing for the astronomical content (and Vallee, a prominent ufologist, actually started out as a computational astronomer himself) somebody had a very broad mind!

A poignant relic from the space exploration exhibit: a heat shield tile from the space shuttle Columbia.

The last photo I took in Wellington, back down on the waterfront: a mad cyclist. By now the weather had definitely closed in, and as it turned out my flight home later that day was delayed by five hours. But at least there was no earthquake!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

JDK

I like my Tiger Moths to have 'James' painted on them!

Why a Hurricane? I agree with your question, but of course arguably New Zealand's greatest military aviator flew a Hurricane while commanding No.11 Group in the Battle of Britain, painted as 'OK-1' - Air Marshall Sir Keith Park. There is a replica Hurri on a stick at MoTaT in Auckland in his colours.

The other aircraft is not a York (the portholes are above the wing, in particular). I would guess that, like in stamp design, a generic aircraft may have been specified (which contradicts what looks pretty 'Hurricany' to me in the same medallion). It's also odd that it's definitely a transport, rather than a bomber, which you'd expect.

Erik Lund

The cyclist isn't mad. There's nothing like a bracing peddle through the rain. Clears the mind, gets you out in nature, spices up the day with a bit of hypothermia and a few chillblains. Everyone should do it. Builds character! And as you stand, shivering, in front of the mirror at home, trying to shed a soaking wet tie with shaking hands, you can take comfort in knowing that you're ever so much holier than thou.....

Okay, he's mad. Other than that, great photos, Brett. I'd like to see a really careful comparison of bilingualism in Welsh and New Zealand signage, though. If I'm right, they'll be doing very different work.

Errolwi

Many more RNZAF members served overseas in the RAF than the RNZAF. More died in the RAF too. Hurri a good call, echoes of the Battle of Britain, rather than yet another Spit! Mustangs were postwar in RNZAF service. I agree on the Dak, however.

Brett Holman

Post authorJDK:

Well, it's not an accurate depiction of a York (only two tail fins, for another difference), for sure. But I can't think of anything it more closely resembles, especially allowing for artistic license -- e.g. maybe the artist moved the portholes above the wing to make it clear that it was a transport, not a bomber. (Which as you say, would have been more representative, and I wonder if the moral question was the reason why this wasn't done.) If the artist wasn't interested in accuracy (and the hardware in the reliefs representing the other services seem, if anything, even less identifiable with anything actually existing in NZ service), then Park's Hurricane may indeed have been an influence, even though he was pure RAF and never served in the RNZAF, as far as I know.

Erik:

I'm sure you're right about the bilingualism, but you'll have to ask somebody else for a careful study! The differing demographic paths of Welsh and Māori speakers would obviously be important; the latter are a significantly smaller minority. On the other hand, Māori gained official language status a few years before Welsh (i.e. the late 1980s rather than the 1990s). Anyway, Australia has only one official language so I'm not criticising.

Errol:

I was hoping you could explain it all for me! But thanks for pointing out my Mustang mistake. Fair point about the proportions serving in the RAF; it's not just about national formations.

JDK

The prototype York had two, later three fins, but it's not a York. Either as an accurate representation or as a modified one. You could, just as well, argue it's a transport Consolidated Liberator (LB-30) The similarities and differences add up to the same number of items, such as the York's distinctive, noteworthy, square section fuselage against the Liberator's oval which fits the representation, and the Liberator had two shield endplate vertical stabilisers.

What it does look like is the generic transport aircraft of the future 1945ish. There were numerous designs and artists representations that fit this configuration, in adverts of the period. I think this is definitely not meant to look like a real machine, and supporting this, note the artist has chosen to leave any power-plant out of the machines in the left of the illustration.

Also the other plaques are an odd mix, with a generic British-style truck cab in the army one, identifiable Thompson and Lee Enfield guns, but a generic tank, not like any real one, more like a toy 'generic' tank.

Errolwi

Well you have NZers in the RAF/RN FAA, and RNZAF members seconded to the RAF/RAN FAA, and RNZAF members in the actual RNZAF. And the RAF ones can be in standard RAF squadrons, or Article XV (NZ) squadrons (which may actually have had a majority of UK aircrew), or a squadron whose aircraft were paid for by the NZ Govt, with a large majority of NZ aircrew, but not officially a (NZ) squadron

Errolwi

You're right on Park, he was NZEF, then Royal Artillery, RFC-> RAF.

By the way, Freyberg was NZ Territorials, Royal Naval Division (after walking up to Churchill!!), standard British Army, seconded/assigned 2 NZEF.

Yvonne Perkins

What a comprehensive post! I was struck by the signs on the old buildings being renovated. 'Heritage and Seismic' protection are inextricably linked in Wellington.

TF Smith

Speaking of the Commonwealth armed forces in WW II, I was reading one of the US Army "Green Books" recently and found General Order No. 1 from the Southwest Pacific GHQ - basically, MacArthur taking command - dated 18 April 1942.

MacArthur uses the signature "General, United States Army, Commander-in-Chief" (meaning of the theater, presumably) and lists Blamey, Brett, and Leary as the Allied commanders of the respective land, air, and sea forces; Wainwright is listed as commander of "US Forces in the Phillippines" and Maj. Gen. Julian Barnes of "US Army Forces in Australia." Richard K. Sutherland, although not named in the Aug. 18 order, was named chief of staff.

The next few pages discuss the staff, and George C. Marshall's request that MacArthur appoint "a number of the higher positions" go to Australian and Dutch officers. MacArthur did not name any Allied officers to the senior (Deputy CoS, G-1 to G-4, Signals, Engineering, AA, AG, etc.) staff positionjs; they were all Americans (and all AUS, of course; no USN need apply).

MacArthur's response to Marshall on the question was that "there were no qualified Dutch officers in Australia" and because of the rapid expansion of the Australian forces, particularly the AMF field forces, the Australians did not have enough staff officers to meet their own needs.

Obvioulsy, this was all to MacArthur's desires, but given the reality of the expansion of the Australian army OOB, presumably there was something to it...but if Mac was a little more "Allied" in his outlook (or "joint" - no USN officers were in the senior staff, either), who was in Australia (as opposed to the Med or UK) who could have filled some of the staff spots without weakening the Australian mobilization in 1942?

These are the "possible" billets, with the US officers who filled them, historically:

Deputy Commander in Chief, SW Pacific Area (not a position that was created, historically, but strikes me as something that couold have gotten a senior Allied officer into a useful slot)

Chief of Staff - MGen. Richard K Sutherland

Deputy COS - BG Richard J. Marshall

G-1 - Col. Charles Stivers

G-2 - Col. Charles Willoughby

G-3 - BG Stephen Chamberlin

G-4 - Col. Lester Whitlock

Signals - BG Spencer Akin

Engineer - BG Hugh Casey

AA - BG William Marquat

Chamberlin and Whitlock had come to Australia with Julian Barnes; the others were all from the Bataan staff.

Any thoughts? Blamey as deputy c-in-c, and someone else (Savige?) as Alllied ground forces commander? Bostock as deputy c-in-c?

Brett Holman

Post authorYvonne:

Yes, and the quakes just keep on coming! Hopefully they're over for now. All buildings will crumble into dust one day, but NZ's are perhaps more vulnerable than most.

TF:

I'm not the best person to ask! Bostock could be a good choice, but I would think that Savige would have been a bit too junior at that point for such a high command; he'd only just become a division commander, having had a brigade in the Middle East. One obvious possibility would be Lavarack, who had taken over from Blamey as I Corps commander and by this time was back in Australia in charge of First Army (defending Queensland and NSW). He was experienced and seemed to have been well regarded, but also underemployed. Maybe also Bennett, who had commanded 8th Division in the Malayan campaign and was also now relatively idle as III Corps commander (Western Australia). But then he was probably tainted by the circumstances of his escape from Singapore.

TF Smith

Brett -

Thanks for the response; appreciate it.

Given the internal dynamics of the AIF/AMF, RAAF, and Curtin's government, what do you think would have been the most accepted by the Australian decision-makers? Put aside MacArthur's wishes; assume GCM would have ordered him to accept an Allied "deputy" area/theater commander. I presume V. Adm. Helfrich (who appears to have been the most senior Dutch officer who made it out of the NEI) would not have been acceptable to the Australians, much less MacArthur; same goes for Adm. Hart or Vice Adm. Glassford of the USN.

So would you suggest Blamey as an Allied deputy theater commander, under MacArthur, and Lavarack as Allied ground forces, including (presumably) the New Guinea force/sub-theater when it became necessary? Or Bostock as deputy theater commander, and Blamey as ground forces/New Guinea commander?

From what I know of Bennett, his billet in WA was probably about the most he could expect (and is sort of surprising, at that; I would have expected him to sidelined to a depot or VDC command somewhere after Malaya); leaving one's troops behind during a negotiated surrender is pretty suspect, honestly.

One can make the comparison with MacArthur, but MacArthur at least was ordered out of Corregidor at FDR's direction, and well in advance of the surrender; Bennett's actions strike me as inexcusable for any officer, and especially a general officer responsible for the safety of tens of thousands of men.

Best,

JDK

I've no familiarity with senior appointment military mechanisms. However a cursory look at the reality of senior RAAF appointment and management to the 1950s from AFC beginnings show a stunning - and I mean stunning - level of incompetence and playground-level feuding by otherwise grown men.

Probably the nadir (though their are other candidates) was appointing the wrong man because they muddled air force seniority or even the name of the candidate.

Note, when reading the linked piece, Jones and Bostock had been friends and working colleges for 20 years!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Bostock#Rivalry_with_George_Jones

Laying theory on this reality added to MacArthur's 'approach' ~ahem~ might be sensible, but hasn't a relation to the real ('you couldn't make it up' level) dynamics, surely?

TF Smith

Thanks for the link; interesting reading. Sounds like Blamey was presumably the only candidate for a "deputy" theater/area position, with Lavarack in the ALF command position that Blamey held historically.

All the belligerents had trouble with mobilization and technical change, especially the Western Allies that did not have peacetime national service - of those, however, the US and UK both seem to have managed things pretty smoothly, building on their World War I experiences.

My guess is that - along with simple resources - the US and UK also had an advantage in that they pursued total mobilization, unlike the (for example) the Commonwealth countries that all proceeded with fundamentally limited mobilizations - the AIF/AMF divide in the Australian Army, for example, which was parallelled by similar "volunteer/conscript" divides in the Canadian, South African, and New Zealand mobilizations.

Obviously, this had a fair amount to do with internal politics in all four dominions, but still, it does point out that different realities of mobilization between the US/UK and the dominions.

Best,

Brett Holman

Post authorI see it as being due more to the funnel effect of the post-WWI demobilisation combined with the inherently smaller nature of the Australian (etc) militaries. A lot of talent and expertise emerged in WWI and received rapid promotions, but there just wasn't room for them in the interwar militaries, so they had to leave (as Blamey did eventually, before returning in 1939) or fight over the few senior postings. So there was a lot of bad blood (and Blamey's enemies accused him of being political, backstabbing, etc, too). At least in the interwar British and American militaries there were more opportunities for imperial postings, diplomatic roles, or even challenging administrative/organisational/planning work; and even the prospect of actual fighting from time to time. So it was easier to hold on to the better officers (though even then there were problems -- look at Mitchell, Liddell Hart, Fuller, even MacArthur himself with his move to the Philippines). By 1942 this had eased somewhat as new talent had begun to rise, but the senior prewar prospects were still the most likely picks for high command.

TF Smith

Fair points, although I'd guess the option of tranferring/remaining with the "British" services (akin to Park, Brand, and Freyberg, for example) preserved some of the Commonwealth talent that otherwise would have left active duty - although that opened up other potential avenues for conflict...

Thinking of the New Zealanders, if a similar "deputy theater commander" position had been ordered for the South Pacific Area (as opposed to the Southwest Pacific), I presume Park and/or Freyberg would be the favorites?

Best,

TF Smith

One point on MacArthur and Mitchell - first off, Mitchell removed himself by resigning his commission in 1926, after the court-martial; he actually could have returned to active duty in 1931, after five years on half pay, if he had not resigned. Given FDR's election in 1932, it is entirely possible that if he had stayed in the Army, he might have been rehabilitated. Of course, his death in 1936 removed any question of further service.

MacArthur is an interesting case; he was only 55 when his term as chief of staff ended in 1935, and technically could have remained on active duty, at his (then) permanent rank of major general, even under Malin Craig and then George C. Marshall as chief of staff, but he chose not to...

There were contemporaries who chose to remain on active duty in a similar situation; one example is Maj. Gen. Stephen Ogden Fuqua, who served as chief of infantry in the early 1930s, reverted to his permanent rank of colonel, and served (very effectively) as the senior US military attache and observer in Spain during the Civil War, before finally retiring in 1943.

MacArthur, because of his politics, was always handled with kid gloves; and there were positives and negatives in that during WW II, both for the Allied cause generally and the Southwes Pacific theater specifically.

Which raises the question of whether a different theater commander in the SWPA would have benefitted the Allied war effort, who that could have been given the realities of 1941-42, and where MacArthur might have ended up, otherwise.

Which in turn raises the question of the significance of the Southwest Pacific theater campaign as it was fought by the Alllies in 1942-45...I'm not certain what the current thinking among strategic thinkers and historians in Australia is today on that question.

Best,

Brett Holman

Post authorAbsolutely. Goble, for example, spend the latter half of the 1930s seconded to the Air Ministry and then Bomber Command. Possibly this gave him ideas above his station, since he resigned as RAAF CAS in 1940 over differences of opinion with the government. And was replaced by a British officer.

Oh, we don't do strategy here! The forthcoming collection edited by Peter Dean, Australia 1943: The Liberation of New Guinea (2013) might have something to say on that question, and since it follows on from Australia 1942 I assume there will be an Australia 1944 and an Australia 1945 to follow...

Errol Cavit

Thinking of the New Zealanders, if a similar "deputy theater commander" position had been ordered for the South Pacific Area (as opposed to the Southwest Pacific), I presume Park and/or Freyberg would be the favorites?

I'm no expert, but I would have thought a air force rather than army officer. Park and Freyberg had both been in British service since WWI. Once Park recovered from his post-BoB treatment, he was rose to Allied Air Commander, South-East Asia - I hadn't realized he was considered to command the RAAF!

AVM Isitt, RNZAF signed the Japanese Surrender.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonard_Monk_Isitt_%28RNZAF_officer%29

Brett Holman

Post authorThat's good enough for me, we're now claiming Park as an Australian.

TF Smith

Thanks for the heads up re the Dean book; sound like something worth looking out for. Is there a reason you don't "do" strategy?

My own take is that with the IJN's only truly strategic weapon was broken at Midway, Australia had the resources to defend itself quite capably (given some L-L), as was proven at Milne Bay and (more or less) at Imita Ridge (granted, WATCHTOWER influenced the withdrawal, but it seems Horii's force was pretty much spent), so the question is whether there was any true need for the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific offensives in 1942...

I'd argue no.

Best,

Errol Cavit

we're now claiming Park as an Australian

So we've got Coningham then? Not his dad, obviously!

Brett Holman

Post authorTF:

I was being a bit glib; of course there are some Australian historians who happily wade in to strategic matters. I guess I was referring more to a longstanding complaint of mine about the understanding of Australian military history in general, in which we focus on the small stuff and ignore the big picture. I wrote something about it a few months ago. Though it has to be said that it goes well with our traditional strategic posture -- supplying troops to fight for a larger power on the assumption that they will help defend us if necessary. Ours not to reason why...

I don't think there's any question that Australia could have defended itself in 1942. Even before Midway Japan lacked the resources to carry out a full-scale invasion; a raid in force would have been messy but ultimately futile; a submarine campaign in Australian waters would have stretched the navy but then IJN doctrine didn't care much for commerce raiding. But we were certainly glad of US assistance at the time!

Errol:

No, it doesn't work like that. Obviously.