WILL THEY BE A COMMON SIGHT?

Officers of the St. Johns Ambulance Brigade, who, in their black and white uniforms, are familiar and friendly figures to Londoners, are now preparing for the possibility that grim and terrible duties may one day fall to their lot. A number of them have recently received instruction in a hall beneath one of London's biggest blocks of flats in methods of first aid in the streets, in the use of shelters and airlocks and the gas-proofing of private premises. A group of them is here seen clothed from head to foot in anti-gas equipment

These photographs are from the fourth of a series of articles on the future of aerial warfare: Boyd Cable, 'If war should come', in John Hammerton, ed., War in the Air: Aerial Wonders of our Time (London: Amalgamated Press, n.d. [1936]), 201-4. The preceding articles were 'Death from the skies', 'The doom of cities', and 'New horrors of air attack'.

Cable's article concentrates on two aspects of the next war. The first is life after the exodus from the great cities expected after a knock-out blow from the air. This happened to an extent even after the air raids in the Great War, and Cable says that it is 'Beyond question' that next time 'the increased horrors will augment the terror and the urge to get into the country', which will become crowded with refugees. But in seeking safety from the bombs they will be exposing themselves to the danger of starvation and disease:

Obviously, if no more than one or two million people are spilled out of a city into the miles of country around it, the highly developed system of sanitation and essential supplies to which they have been accustomed will be entirely lacking [...] In such circumstances, disease and epidemics would spread like wildfire among them.

Even in the best of circumstances, it would be next to impossible to care for such a flood of people. In wartime, the problem would be insoluble: the attack would probably come suddenly, giving authorities no time to prepare, and enemy bombers would also be attacking the ports from which the food must come. Providing clean drinking water for hundreds of thousands of refugees would also be impossible. In a week, starvation and typhoid would be stalking them.

And there would be no guarantee that the enemy would not attack them even dispersed in the countryside:

Bombers would simply rain incendiary bombs on any patch of woodland and set it blazing from end to end, or drench the wood with poison gas which would contaminate trees, grass and earth for weeks, and turn it into a death-trap and charnel house.

Add to this the horror of bacteriological warfare. Cable admits that this presents difficulties for the aggressor, as epidemic infections are no respecters of national borders and may end up infecting those who spread them. But

Such a consideration is not so likely to deter an attacker of Britain, however, for it would be a simple matter to prevent any infected person or animal from carrying the germs from their country back to the Continent.

Also, he notes evidence that nations are anyway prepared to take the risk, Germany in particular. He notes (quoting here Dr Gertud Woker, a Swiss professor of chemistry) 'the notorious Zurich "bomb and bacilli" case' during the last war; 'a machine for spraying disease germs' said to have been made 'under the direction of Herr Himmler, Munich police commander'; and the secret German experimentation with germ circulation in the Paris Metro, which caused a sensation there in 1934 (oddly, he doesn't mention that the experiments were supposedly carried out in the London Underground too).

Still, Cable concludes on a relatively optimistic note:

Certainly town populations will be safer in the open country than in their own homes, if they can keep moderately scattered. It might even pay an enemy, as a military measure, to leave them reasonably unmolested while they keep out of the towns, because a people living in fields and forests would stop all munition and war work.

FAR WORSE THINGS MAY COME

"Darkness and composure," which it was suggested were the best means of countering the first Zeppelin raids, will be useless against poison gas attacks from the air. There will be a headlong flight from the gas-contaminated cities to the open country, and such scenes as this, when the Belgian people fled before the advancing German armies, will be repeated on a vastly greater and more terrible scale, with the added horror of panic

EVERYWHERE THE FEAR OF GAS

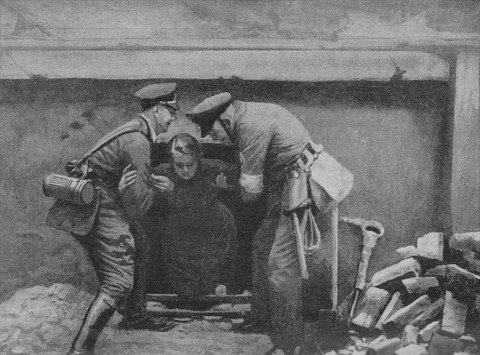

It is obviously impossible to reproduce in peace time the horrible conditions of an actual attack by aerial raiders dropping gas bombs, but in nearly every European country the people of the cities have gone through a course of anti-gas drill, not only for practice purposes, but with the idea of familiarizing the public with such possibilities. Here are girls leaving a house in Munich that has been filled with gas. They wear anti-gas clothing but are not fully equipped with gas masks. Below, first-aid men are helping a woman from a bombed house during a mimic raid on Berlin

HE CARRIES POISON

The gases which would be used in chemical warfare of the future cling to the ground for many hours and precautions must be taken lest the stretcher-bearers should take them into the hospitals. Here their boots are being cleansed of gas during anti-gas instruction course at Salisbury

AS THE ITALIANS DO

In Rome anti-gas precautions are very thorough. Here, during gas drill, chemicals are being spread on the steps of the Ministry of Defence as antidotes to the fumes left by gas bombs

There's a disconnect here between the illustrations and the text. Only the one showing a press of Belgian refugees in 1914 actually pertains at all to one of Cable's topics, giving an idea of what the exodus would be like. All the rest are about precautions for chemical warfare, not biological warfare; and there's no attempt to portray the starvation- and disease-ridden crowds of scared Londoners hiding in Epping Forest. Probably because these things are difficult to represent (what would they choose? Scientists looking through microscopes? Mass starvation in India?) but also because, for its part, bacteriological warfare was not actually high on anyone's civil defence agenda. Also, gas and germs tended to be elided in the public mind, somewhat. Also, pictures of people in gas masks are so vivid and striking that it was an easy an effective way of getting the message (i.e. be afraid!) across. In fact, so vivid and striking that I couldn't resist putting the ambulance men at the top of the post, even though they don't appear until the third page of Cable's article.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Pingback:

Downward, inward persuasion — I – Airminded