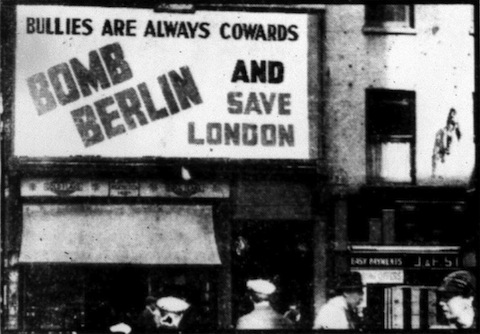

This photo appeared on the front page of the Sunday Express on 6 October 1940, a month into the Blitz. A caption explained, or rather asked:

WHO PUT UP THIS POSTER?

This mystery poster has appeared in the streets of London.

It is about six feet high and ten or twelve feet across, and bears nothing to indicate its authorship. No one knows who is paying for it.1

In just nine words the poster presents a very simple argument in favour of the reprisal bombing of Germany:

BULLIES ARE ALWAYS COWARDS

BOMB BERLIN AND SAVE LONDON

By bombing Berlin, London would be saved from the Blitz. The German (or perhaps just the Nazi) bullies, being cowards, will not be able to take it as well as the British and so will crack first.

I don't know how many people the poster influenced. But some who might have seen it were already leaning the same way, judging from letter columns in the press. For example, H. H. G. Lewis wrote to the Daily Mirror from Southwark saying that he and his friends 'are of the opinion that we should bomb Germany in "retaliation" for what has been done here".2

It appears to be the only way of stopping this Nazi mass-murder which will undoubtedly increase if Sir Archibald Sinclair's present policy of "no retaliation" is adhered to.

The basis of this view was that despite their murderousness the Germans were capable of being deterred. But as Sinclair, the Air Minister, had publicly declared that the RAF would not carry out reprisal bombings for German air raids and his critics charged that this enabled Hitler to bomb London without having any fears for Berlin. The Mirror ran a campaign against Sinclair and encouraged readers to write with their views; to Lewis it replied

Do you think there's a soul left in the country -- barring Sir Archibald -- who wouldn't like to see Berlin in ashes? It should be bombed to blazes and after the war we could have cheap week-end excursion to see it! At least, that's what our readers tell us!

In fact there were plenty of people who agreed with Sinclair, and even on the pro-reprisals side there was a wide diversity of opinion. John Gordon, the editor of the Sunday Express, was a strong supporter of reprisals, but instead of bombing for deterrence he wanted bombing for victory:

Get every bomber we can spare over Germany every hour of every night. Go for the big towns; smash their electricity works and their gas works; smash their railways; block their roads; keep their population awake waiting in terror for your coming.

Make their nights a misery and their days a torment of inconvenience. A few weeks of that will soon make changes in their morale.3

This aligns very closely with some pre-war conceptions of the knock-out blow from the air.

But although Gordon called for the RAF to 'start as Hitler started the Battle of Britain[,] by concentrated bombing attacks on his cities', he denied that this meant 'indiscriminate attacks on civilians' but only 'attacks on the amenities of civilian life. And these are military objectives'. That was a common distinction: it was one thing to terrorise civilians, another to intentionally try to kill them. But then other writers invoked the concept of total war to argue that the whole idea of a 'civilian' was now obsolete -- for example this leading article in the Mirror:

In a total war there is no distinction between military and civilian. As the King has just reminded us, civilians are in the forefront of the battle. Their gallantry is to be formally recognised.

There is, further, no distinction between a war upon strong arms and trained men and war upon nerves, strong or weak [...] We therefore strike at German nerve-centres (military, industrial) and also, in so doing, at German nerves.

Even here, there is a denial that civilians in and of themselves could be a valid target: their morale was, certainly, but not their bodies.

This reluctance raises a question which seems obvious in hindsight but was rarely addressed at the time: once German civilians realised that they were not actually in bodily peril then wouldn't the morale effect of precision bombing diminish? The reason for this may have been a recognition that civilian casualties were going to be inevitable, even with the most accurate bombing. So while civilians would not be deliberately killed, they would be 'accidentally' killed and that would be enough for morale purposes. Thus a leading article in the Daily Express in April 1941 argued that Berlin was full of military objectives, but 'if by chance a lot of Germans catch it too there will be no regrets'.4

Still others skirted closer to wishing for the deaths of German civilians. Patience Strong, who wrote poems for the Mirror, offered one entitled 'Coventry':

The martyred City, gashed and scarred -- her children slain, her beauty marred -- Still proudly stands, but to the sky -- the very stones for vengeance cry.

As Nations sow, so must they reap -- They, too, for this night's work shall weep -- such deeds their retribution bring -- God speed the Day of Reckoning.5

If that's not explicit enough, then take this letter sent to John Gordon and approvingly quoted by him in his column, mocking the 'naice' (in BBC English) but softhearted types who allegedly ran Britain now:

He [the Sunday Times columnist Q] says, "I would take one German town... and I would bomb it... continuously until it was completely wrecked."

Splendid. But to avoid a flood of protests from the naice [sic] readers of the Sunday Times he said just before: "Let us never deliberately bomb German women and children."

He doesn't say how he proposes to do the complete wrecking job without bombing German women and children!6

That kind of clarity was quite rare from the pro-reprisals camp. It could be that they were refusing to confront the implications of their proposals, but in at least some cases I think there were genuine beliefs that airpower could compel without killing, as I'll discuss in another post.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Sunday Express, 6 October 1940, 1. Apparently a 'Mr. Beabie' admitted to the Sunday Dispatch that he was responsible, but I can't see the original text and I wonder if that should be 'Begbie'. Not that I know who he is either. [↩]

- Daily Mirror, 6 September 1940, 5. [↩]

- Sunday Express, 22 September 1940, 6. [↩]

- Daily Express, 19 April 1941, 2. [↩]

- Daily Mirror, 18 November 1940, 5. [↩]

- Sunday Express, 23 February 1941, 2. [↩]

Pingback:

Airminded · Precisely