[Cross-posted at Cliopatria.]

It's Anzac Day once again. On Anzac Day, Australia remembers some things but forgets others. We remember the sacrifices of the original Anzacs at Gallipoli, but forget that it wasn't only Australians who suffered. We remember the many thousands of young Australians who have fought in foreign wars since then, but forget to ask why they were there. We remember that war can bring out the best in people, but forget that it can also bring out the worst.

One thing we tend to forget is Australia's part in the bombing of Europe in the Second World War. There are a few memorials and exhibits, but when we think of Anzacs we usually think of slouch hats, not flying helmets.

Eight Royal Australian Air Force squadrons served with RAF Bomber Command at various times: 455, 458, 460 (members of which can be seen above arranged in front of -- and on top of -- one of their Lancasters), 462, 463, 464, 466 and 467. Many other Australians flew with RAF heavy bomber squadrons, just as many non-Australians did with the RAAF squadrons. (Often outnumbering the Australians, in fact: when 462 was formed, only one of its aircrew was Australian.) In total, around 10,000 Australians served in Bomber Command during the war, at stations like this one at Waddington, home to 463 and 467 Squadrons for the war's last eighteen months.

The butcher's bill was enormous: of those 10,000, nearly 3500 Australian airmen were killed, out of 10,500 RAAF deaths for the whole war and 39,300 for all three services. That is, one in eleven of Australian service personnel who died in the war did so while serving in Bomber Command. One in three of those Australians who fought their war in the night skies above Europe never came home again. Two hundred men from 463 Squadron were killed in the eight months before D-Day, 130 per cent of its establishment strength.

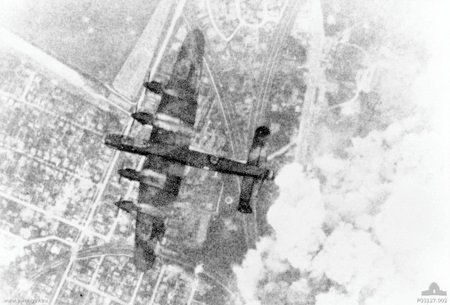

Above is a RAAF Lancaster of 463 Squadron over Normandy in July 1944. One of its engines is on fire and the crew are about to bail out; two were killed and three taken prisoner.

But to focus on just the Australian casualties would also be a form of forgetting. They didn't join Bomber Command to die but to fight. RAAF aircrew and squadrons played an important role in many of Bomber Command's most famous operations: busting the Ruhr dams, the Amiens prison raid, sinking the Tirpitz. But they also took part in all of the RAF's big assaults on German cities: Cologne, Hamburg, Berlin, and so many others.

Above is one of 460 Squadron's Lancasters bombing Freiburg on the night of 27 November 1944, part of a raid which killed about 3000 civilians.

This is Dresden on 14 February 1945, the day after the Allies began their attack on the city. Three RAAF squadrons -- 460, 463 and 467 -- helped to create the firestorm in which 25,000 people, mostly civilians, were killed. At a minimum, the Combined Bomber Offensive killed at least 300,000 civilians in Germany, and many thousands more in occupied Europe. Some proportion of those were killed by Australians -- under British command, true, but with the acquiescence and approval of the Australian government and the great majority of its people. Unlike in Britain, the moral questions surrounding the area bombing of cities in the Second World War have never been controversial in Australia, or even seriously questioned, not at the time, not afterwards. They are glossed over. And when our bomber boys are remembered, just what they bombed is not.

I'm not against Anzac Day at all. It's good to have a day to remember those who fought and those who died for us. But Anzac Day allows us to talk about some things to do with Australia's wars, and not about others. If we remember the great and heroic deeds done in our name, we should also remember those things which are perhaps less comfortable to dwell on. And ask why they happened, and whether they could happen again.

Image sources: Australian War Memorial P03127.002, SUK13470, SUK13775, UK2288, UK2416.

Further reading: Alan Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2001), chapter 5.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Jason Korke

Great post Brett. It's not related to airpower, but I was reflecting the other day on the myth of WW1 unifying Australia when it was really very divisive... arguably few things have ever divided us as much as the conscription debate did at that time.

I was struck by a quote from a 1917 letter from the Victor Voules Brown in France, saying, "Last time you wrote you wanted to know why it was the troops in France did not vote for conscription. I told you as short as I could perhaps it was censored so will tell you again. To cut it short the boys in France have had such a doing of it, that they consider it murder (or near enough to it) to compel anymore to come from Aussie. And then again they consider once conscription is brought in it is the end of a free Australia (No doubt about it John Australia is the finest country in the world to my idea.

When the vote for conscription took place I was in Codford & I voted yes, but dinkum I am like the rest now I have seen it, & wouldn’t compel anyone (barring the few rotters of single chaps that won't come. And of course to get them one would have to get a lot of others, so under the circumstances let them stop at home. It is no good for a peaceful life over there & I can tell you I am not looking forward to the next dose".

I think it's a credit to Australia as it was then that so many people fought tooth and nail against conscription, as there is a big moral difference (in my mind anyway) between a foreign war fought by volunteers and one fought by conscripts. I think these sorts of things are well worth remembering.

JDK

Thanks, Brett, a good post. I was interested in the diversity of opinion in the media today here in Australia, discussing many of the aspects of the nature of the issues around (potentially simplistic) interpretations of Anzac day. I'd agree that the issues of Bomber Command isn't an aspect widely debated or examined in Australia in the way and detail you highlight here.

That said, we published an article defending Bomber Command by Peter Issacson (Peter Stuart Isaacson AM, DFC, AFC, DFM) in Flightpath recently, based on his website's page - and as an Australian Bomber Command veteran he clearly feels there's a question to be answered:

Here: http://www.picommentaries.com/sub2.htm

The Australian War Memorial's 'Striking by Night' display is (in my opinion) a very effective son et lumiere demonstration of what a raid was like, and it does look at the effects as well as the method and costs. I can't think of anything of similar calibre in the UK, Canada, New Zealand or elsewhere in Australia that dramatises and explains this story so well, so there is a place in Australia where the memory and question is (again in my opinion!) well held.

http://www.awm.gov.au/exhibitions/striking/

(There are, of course many worthy and worthwhile displays, memorials and museums across the Commonwealth reflecting Bomber Command's story, not least being the RAF Battle of Britain Memorial Flight's airworthy Lancaster PA474 or the Canadian Warplane Heritage's also airworthy but privately operated Lancaster C-GVRA. But, as with these, it's notable that the cause and effect of bombing is often presented in a one sided way in physical memorials and in museums artefact displays.

I was once privileged to have stood among Bomber Command veterans in an English market town as PA474 flew over. That was an experience which contextualised the need for the debate and respect for those involved first hand in a very real way. It was not Coventry - what if it had been?)

Alan Allport

Excellent post. I have nothing to add other than this is why I read Airminded.

Neil Datson

Another good post Brett.

Jason's last paragraph about conscription reminds me that there were several ministerial resignations over its introduction in Britain. Looking back from this distance that seems almost incredible. The twentieth century saw a huge rise in the power and discipline of the nation state, and - in some important senses - a commensurate fall in its tolerance.

Erik Lund

Great post, Brett.

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks, everyone!

Jason and Neil:

The conscription debates (those won and those lost) are definitely worth remembering; the rifts they caused are suggested by the tendency of war memorials in the UK to list only those who died, where those in Australia list all those who served. And your comments remind me that perhaps I was hasty to say there was no opposition to area bombing in Australia during the war -- there was some in Britain (Vera Brittain et al). I wonder now if pacifists spoke up here as well. I'm curious now!

JDK:

Yes, we are certainly seeing more debate about Anzac Day and what it should mean now, which is all for the good. Historians are also starting to push back against some of the more simplistic interpretations of Australian military history -- UNSW Press has a couple of books out along these lines: Whats Wrong With ANZAC? (Lake, Reynolds, Damousi, Mckenna) and Zombie Myths of Australian Military History (Stockings, ed), one or both of which may find their way onto my bookshelf very soon.

Striking By Night is excellent, from memory (I last saw it not long after it opened) and the AWM has many, many visitors, so it is significant site for these questions. But the very fact that the centre of the exhibition is an bomber would shape its focus, wouldn't it? The sound and light show is more about the experience of flying a bomber mission than it is about living through an air raid. (As I recall, please correct me if I'm wrong!) That's natural enough when you have a superb artifact like G for George. In some ways museum displays are like TV news -- it's not news unless there's vision to show it, it's not history unless there's an object to write a caption for. Or maybe I'm being unfair!

Chris Williams

To be fair on you Aussies, us Brits also condense our memory of the late unpleasantness into bite-sized and easy-to-remember chunks, which are notable for accentuating the positive: the RAF, for example, is very happy to celebrate Battle of Britain Day: no Bomber Command Day as yet. If they did pick one it would probably be the Dams Raid, itself a massive outlier which has received disproportionate attention.

And I'm pretty sure that it's not merely a British empire thing, but a nearly ubiquitous tendency (I have hope for the Czechs, but no evidence): certain national narratives of the memory of war get reinforced and re-broadcast, while others are left to fend for themselves.

I can understand why there's less debate about area bombing in Australia. It was, at the end of the day, somebody else's problem. The mother country took responsibility for the policy, and even if the RAAF (including Bennett? This is not likely) and every Aussie in the RAF had collectively signed a memo protesting at it, that wouldn't have stopped it: although it would have got many of them court martialled.

Were any Australian voices raised about the firebombing of Japanese cities, notably Tokyo? Obviously this was somebody else's problem too, but it was closer to home. I can detect in some British sources a sense of regret and perhaps shame on arriving to inherit the rubble in May 1945: was there a similar feeling in Sept 1945, or did the lack of comparable Australian involvement in the occupation of Japan make it far less likely?

Brett Holman

Post authorI don't think we can evade accepting some responsibility for area bombing just because we were carrying out British policy; that's pretty much the Nuremberg defence. They were Australian men, Australian squadrons, carrying out Australian national policy -- which, as always in Australian warfare, is actually carrying out some other, more powerful nation's policy. And there's the rub.

I don't know what the reactions to the firebombing of Japan were here, but anyway that was a purely American affair. (At one point 460, 463 and 467 Squadrons were assigned to Tiger Force, so if the war had continued past September that would have changed.) Australian forces did take part in the occupation of Japan; in fact most of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force was Australian (and its commander was too). But again, I don't know much about it, though I think the BCOF generally had good relations with the Japanese civilians, so maybe there was some sympathy there?

JDK

Brett said: But the very fact that the centre of the exhibition is an bomber would shape its focus, wouldn’t it? The sound and light show is more about the experience of flying a bomber mission than it is about living through an air raid. (As I recall, please correct me if I’m wrong!) That’s natural enough when you have a superb artifact like G for George. In some ways museum displays are like TV news — it’s not news unless there’s vision to show it, it’s not history unless there’s an object to write a caption for. Or maybe I’m being unfair!

I'd certainly agree with your comments Brett, and it leads to some other comment. Firstly, while the Lancaster is the centre of the display, it (in my opinion) stands well as just 'one bomber'. The display is supported by the use of a real Me 109G making an 'attack' and an 88 flak gun. The film background features some footage of Germans heading to shelters, close and aerial shots of bombed cities and German defences - including radar plotters and those anti-aircraft guns in action. So it's not as one sided as it might be. (The Memorial claims that 'three Messerschmitts' are part of the display, but the 163 and 262 are not integrated into the son et lumiere. The AWM Striking By Night website discusses the role of German civilians (under 'German Defences') but not their losses.)

So it's a lot broader based than it might be, and less 'here's some cool objects, captioned' which most more specialised military museums can tend towards.

While there are a number of 'trench experiences' and dioramas around the world (from the RAAF Museum to the Imperial War Museum) and a number of displays about the aims, objectives and sometimes failings of the bomber campaign, I'm not aware of a 'bombed city experience' in any museum or memorial. (There are 'bombed city' displays in the RAF Museum for instance - tellingly of an English street in the Battle of Britain hall and the effects of bombing on a factory in the Bomber Command hall.) The virtual reality has extended to (nearly) getting shot in a trench but not (nearly) getting cooked in your home.

The simple irony of Bomber Command seems to me to be that there was a drive by organisers and recruits that the W.W.II bomber war would avoid the meat grinder of the Western Front trenches of the previous war - yet the random and incredibly costly body count (to both bombers and bombed, Allied and Axis) was a re-run in many ways of this failure of technology as a solution.

Brett Holman

Post authorThere is one 'bombed city experience' I know of, and (again, tellingly) it's the 'Blitz Experience' at IWM London: there's a recreation of a bombed street, and you sit in the dark inside an Anderson shelter while the sounds of an air raid go on around you. I actually found it a bit disappointing though; as I recall it was confusing as to when the 'experience' started and stopped, and because it was dark it was hard to see things (which, of course, is perfectly accurate!) I don't think there was a guide when I went through it, and people just wandered in and out, so that may not have helped.

I guess what I'd ideally like to see is some sort of translation into museum terms of Len Deighton's Bomber. It's probably 20 years since I read it, and I don't even know how well it holds up as history, but it has stayed with me. It made me consider for the first time that as horrific as the bomber war was for 'our' boys, it was far more so for the civilians being bombed. But national museums and war museums are perhaps not where you would expect such lessons to be taught; perhaps you'd need a peace museum for that.

Chris Williams

My memory of the 'bombed factory' exhibit at the RAF museum (Hendon) is that it does point out 'Even if you can knock down the building, it's hard to knock out a lathe, so production might not suffer'. I might be wrong, though, but if so, it's a significant case of knocking the product.

JDK

I found the 1940 House at the IWM, but obviously missed the 'Blitz Experience', or maybe I just went through at high speed, such things being of (very ~um~) academic interest to me. I like to know they exist, but like IMAX I've better things to 'experience' when in museums.

I think one of the concepts I was groping towards with museums is that it's not common to deal with immediate aftermaths, but the 'experience' and a (much later) historical perspective, rather than the direct effect. (Coming out of the shelter to see a bombed street and dead neighbours.) Rather like why wrecked aircraft are hard to present appropriately in museums.

I have a photo of the caption to that exhibit, Chris, which I'd forwarded to Brett some time ago relating to another discussion. It actually is a much more complex text than you recall, and discusses a number of aspects - de-roofing a factory being easy, damaging plant being hard, but plant left uncovered quickly degraded from being useful due to rust and electrical failure, and further (I can transcribe the text if it's of interest).

Again rare in going into the actual 'how' rather than the normal simplistic 'it got bombed'.

Pingback:

Airminded · Oneupairmanship

Pops

Ref JDK post on 4 May, 1234pm, Although not in Europe, there is a museum in Japan, the Osaka International Peace Center, that has a number of displays, dioramas, works of art and personal recollections by Osaka citizens of the bombings of the city during WWII. For some idea of what is available, see the English language guide to the museum at:

http://www.peace-osaka.or.jp/pdf/pamphlet_en.pdf

Also of note is a relatively recent website project, Japan Air Raids, that is bringing to light much of the Japanese civilian experience whilst under aerial attack in WWII. See the site at: http://www.japanairraids.org/

Brett Holman

Post authorPops:

Thanks for those links. Japan Air Raids is a really excellent resource, particularly with all the primary source documents they've uploaded. Something similar for Europe would be nice!

JDK

Hi Pops,

Many thanks for that, it certainly adds to the concepts under discussion.

Not to detract from the good reasons behind such themes being shown in general it is no surprise that this is in Japan, where a focus on their victim aspect of W.W.II avoids some of the harder questions of Japan's responsibility for initiating that conflict.

Leaving aside any moral judgements of that for a moment, it is a very thought-provoking counter to one of Brett's initial points about responsibility, and how that's often finessed in museums and history presentation.

Pingback:

Airminded · As it was

Roger Bellamy

As a Brit whose father and uncle were in the RAF during the war (and my uncle's uncle was at Gallipoli 25/4/15), perhaps that quote of George Orwell's puts the debate in context;

" War is always Evil, but sometimes it is the lesser Evil."

It was a fight to the death, only narrowly won. There was no benefit of hindsight, nor time, nor any suggestion of 'minimum force', which in itself is a civilian concept. It was bad, it happened, but who in 1944, when Germany was introducing technology well in advance of our own capabilities, were we supposed to do? Negotiate? With Hitler?

The irony is that better armed forces and stronger resolve in the mid-thirties might well have deterred him. But that we didn't have. To a degree, Dresden was the ultimate fruit of inter-war pacifism.

Brett Holman

Post authorRoger:

Thanks for your comment. I largely disagree. It simply not true to say that there was no 'suggestion of "minimum force"'. For example, the question of whether German civilians were legitimate targets was hotly and publicly debated during the Blitz (I've written an article about this, which you may not have access to, but I've also hashed out many of the issues on this blog). The debate was not resolved, though by default the consensus was the let the RAF keep doing what it said it was doing, i.e. bombing military targets, a claim which implicitly recognises a special status for civilians. Ridiculing negotiation as the only alternative to area bombing is a strawman, especially since you single out 1944, which is not only the year of D-Day and Bagration, but also, ironically for your argument, the year that Bomber Command was employed in what many have argued was its most effective use, attacking oil and transport targets rather than cities per se (and which Harris opposed). To suggest that the only alternative was negotiation is, frankly, absurd. Moreover, you exaggerate Germany's technological lead. I presume you are talking about the V-1s and V-2s, but the many thousands launched by the Germans killed less people than the Dresden raid, or the entire Blitz for that matter. Besides which, Allied bombing wasn't a response to them (the other way around, actually); it had been going on since 1940 (1942 for area bombing as policy). I can agree that Hitler 'might' have been deterred by stronger and more determined opponents in the 1930s. But only because you said 'might', and it wasn't pacifism that prevented it from happening.

Yes, of course we have the benefit of hindsight, but that's also a burden. It's too easy to go from 'this is what did happen' to 'this is what must have happened'. History isn't that deterministic.

Bob Meade

Thank you, Brett. Well written, as others above have said.

G for George was just as important an exhibit piece before the sound and light show. My first visit to the AWM was in 1978 with my parents - my father is a veteran of the Second World War, my mother lost her beloved brother in New Guinea - so it had some poignant moments. G for George was just as dominant then as now and because war/action films were a television staple of every Australian childhood the Hollywood version of bombing missions was firmly imprinted in my mind. I remember too my mother scoffing at the depiction of Japanese soldiers as being myopic and wearing spectacles.

Pingback:

The one day of the century | Airminded

Brett Holman

Post authorBob:

I never got to see the old exhibit, but my own mother certainly has vivid memories of seeing G for George when she visited the AWM on a school trip (I won't say exactly when, but it would have been well before 1978). I gather that awareness of the Australian contribution to the bomber war was far higher then than it is today - not exactly a surprise, but tracing that evolution make a nice study as a counterpoint to the resurgence of Anzac.

Pingback:

A day to remember – Airminded

Steve Larkins

War has shaped human history like no other occurrence.

It is a fact that the initial aggressor is always better prepared than the victims of it, and that few people engaged as combatants in its prosecution at the outset, survive to see its end.

The cost of losing a total war doesn't bear contemplating.

Area bombing of Germany in WW2 has come in for a lot of criticism. I have a simple question - what else was Britain to do? It had no other survivable means of striking at Germany, and had itself been victim of Luftwaffe raids. It lost a huge proportion of its land army in the futile defence of France in 1940 and was sticking its fingers in dykes across the Mediterranean and then of course in the Far East through 1941-2 and well into 1943. It could have sued for peace, surrendered and been occupied or hung on and mounted costly, futile and premature amphibious raids and landings frittering away limited materiel and personnel resources and having civilian morale crumble behind it, or finally, just twiddled its thumbs. Britain was also under pressure to do something to relieve the Nazi pressure on Russia. Armchair warriors and philosophers excel at being wise after the event. Britain did what it had to do to survive and the rest of the free world should be eternally grateful they did. None of it would have happened if Germany and Japan hadn't gone to war in the first place.

Brett Holman

Post authorI think the argument 'what else could Britain have done?' other than bomb German cities is less and less effective the longer the war went on. In 1940 and 1941, sure. Britain did not have the resources to invade the continent, but nor had it been defeated; there had to be some way to keep fighting. In 1942 and 1943, maybe. The US was now in the war and invasion was definitely foreseeable, if not just yet; on the other hand, the Soviets desperately needed some form of help. In 1944 and 1945, no; the invasion was imminent (or occurring) and those resources could have been used for other things (and when they were, in attacking German transport networks in 1944, they were highly effective).

The problem by then, of course, was that Bomber Command was locked in to area bombing and it was difficult to shift. 1942 was the key year, when area bombing became formal policy, which was then confirmed at the Casablanca conference. But even then it wasn't inevitable; strategy could have changed later, if the will had been there.

And yes, we have hindsight; as historians, that is always our privilege and our burden. But it's not just people afterwards saying that things could/should have been different: even in the middle of the Blitz there was a fierce public debate about whether it was moral, effective, or both to bomb German cities in reprisal. I've written an article on this topic, which you can read here.