Here's a question of terminology which has been bugging me for some time. The Munich crisis in September and October 1938 is a well-known historical event. But the name 'Munich crisis' is misleading, because the crisis was building long before the word Munich was ever associated with it. Munich had nothing to do with the Munich crisis at all, except that it just happened to be the place where Chamberlain, Hitler, Mussolini and Daladier met to resolve it. (So 'Munich conference' is fine, as is 'Munich' as a shorthand for the betrayal of Czechoslovakia.) 'Czech crisis' would be better, but that's usually reserved for an earlier flap around March 1938. I tend to prefer 'Sudeten crisis', which has the virtue of indicating what the crisis was actually about. On the other hand, nobody at the time seems to have spoken of the Sudeten crisis; usually they referred to the Czech crisis, and very occasionally, after the crisis had passed, the Munich crisis. And Munich crisis is certainly the preferred term today.

So what say you? Feel free to make arguments in comments.

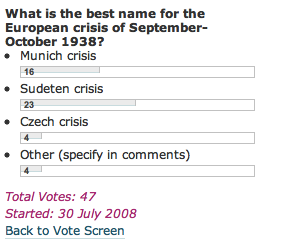

Edit: I have removed the poll plugin for security reasons. But here's a screenshot of the poll results as of 22 November 2011:

Next up: 'Crisis' vs 'crisis'. You be the judge!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Chris Williams

Second Czech Crisis - March 39 being the Third.

Heather

I'm going with Sudeten Crisis. Spookily enough I've been reading a couple of books I acquired a short while ago that cover this particular period. Both are recommended to those interested in why the Second World War happened.

The books are "The Dark Valley" by Piers Brendon and "The Approach of War 1938-1939" by Christopher Thorne (part of a series called "The Making of the Twentieth Century").

Though my particular interest is the period from the Phoney War to the start of the London Blitz, understanding the how and why the main conflict happened is fascinating.

Ricardo Reis

I prefer sudent crisis and I think thats the way its called around here (Portugal). Which lead me to another question: what differences are there in terminology that result from the country where they are spoken about? Same historial events sometimes are referred by diferent names in diferent countries... so... only Anglos should answer your questionaire?

Brett Holman

Post authorChris:

I like that, actually. But maybe it would seem a bit pretentious for me to go around in my thesis relabelling three crises like that instead of just one?

Heather:

I read The Dark Valley when it came out, it's very vivid and covers a lot of ground (some of which often gets neglected -- all the stuff about Japan was new to me, anyway). May have to have a look at Thorne, thanks for that.

Ricardo:

It's not a very scientific survey so I think you should go ahead and fill it out if you like! It might be interesting to see a comparative list of the names for various events in different countries. In Russia, WWII is known as the Great Patriotic War (or was, or so I have been told), which presumably says something about how the contributions and activities of the western Allies were minimised.

Chris Williams

Student crisis is what happened at Eben-Emael...

(Apologies for obscure fallschirmjager pun.)

Brett Holman

Post authorOh dear!

Ricardo Reis

Probably with Putin in charge it still is The Great Patriotic War...

Heather

Brett, you may find Thorne's book covers more or less what Brendon's does, but it does concentrate on the European events. It obviously shares sources, but Brendon's book has a much wider scope, as you say. It really filled in may details of the global situation during the 1930s, and how it was almost inevitable that the countries that moved toward extremist political views during that period would end up in a war.

Nemo

There are some great audio clips from 1938 radio braodcasts about the Sudeten Crisis (going far beyond just Chamberlain's "Peace in our time" soundbite) at the following page:

http://www.otr.com/munich.shtml

Gavin

Knowing what to call things is always difficult. I often tend to go with the one that most people know even if it's misleading. For example, I argued (following Mark Kishlansky) that the New Model Army might not have been quite as new as many people think, but I still carried on calling it the New Model Army. I wrote a whole post somewhere about what to call the English/British Revolution(s)/Civil War(s). I usually tend to stick with English Civil War because that's what my own work is about - south-eastern England during the First Civil War (which wasn't the first civil war to ever happen in England).

Numbering things gets even more confusing. It seems like Gulf War numbers have got right out of sync. Back in the 80s Gulf War meant the Iran-Iraq war but then in 1991 that came to be the First Gulf War and Desert Storm the Second (or at least that's how I thought of it). Since the present one kicked off people have been talking about Desert Storm as the First Gulf War and this one as the Second.

And I'm really confused about what to call the people who lived in North America before Columbus or the Vikings arrived.

David Edgerton

Nice point Brett. If we are speaking about British responses it is worth making the point that the term 'crisis', much overused here now, was very clearly associated with the events of Sept/Oct 1938. So 'crisis' is right. As to the first term, I have been noting recently that (as Brett says) there was no 'Munich crisis', but lots of people referred to the 'September crisis', but I don't have any sense how long this lasted.

Brett Holman

Post authorNemo:

Thanks!

Gavin:

I agree that it's good idea, in general, to stick with previous nomenclature if it's well-established, even if it's misleading. (The Big Bang is an example that comes to mind ... it's evocative but misleadingly so, and was coined by an opponent of the theory to disparage it!) But I think Sudeten crisis has about enough currency to not confuse people? Google suggests "Munich crisis" is used about 10 times more often than "Sudeten crisis", which I thought is a surprisingly low ratio.

David:

I like 'September crisis' too (the fact that I like all the alternatives probably says something about how much Munich crisis annoys me!) It harks back to the July crisis of 1914. Was there an August crisis of 1939? Good point about 'crisis' itself. Madge and Harrisson discussed at some length the word itself and the way in which it attached to the, well, crisis in their Britain by Mass-Observation (1939).

Paul Shafer

You are correct. This is clearly pointed out in Shirer's 1969 Book "The Collapse of the Third Republic." However, it was really a crisis of Great Britain and France. France was too scared to act on her own and kept blaming GB. If France had acted, beyond just putting her army on alert, GB would have had no choice but to send her 130+ bombers over Germany to scare Hitler. (Of course, the US was kept abreast of the whole affair and did not help at all...the US could have sent additional bombers to GB and France in 1938). It did not help that before the "crisis" Goering wined and dined the Head of the French Air Force and even took him to see the jet engine test bench. Vuillemins told Gamelin and Daladier that "the French air force would be wiped out in two weeks" based upon the hype that he was permitted to see by Goering.

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks, Paul.

Paul Shafer

Ambassador Coulondre of France wrote in 1938 after Daladier and Chamberlain abandonned the Czechs, "Munich tolled the bell for a certain France, la grande France of former times and even 1914.....The tolling of bells do not kill a sick man! They announce his death. The accord of Munich did not

provoke the fall of France. It registered it!"

Two years later Coulondre was proven correct.

Pingback:

Airminded · Thursday, 29 September 1938

Pingback:

Airminded · Post-blogging the Sudeten crisis: thoughts and conclusions

Adam

Dear colleagues,

If you don't mind listening to the opinion of someone who is a Czech citizen and who sees and feels the whole issue "from inside", I would say that the event is known here (in the Czech Republic) as Munich Crisis or Munich Agreement or Munich Betrayal). Very popular phrase here is also "about us without us". That is also why we don't like foreigners very much, especially if they are from Germany or Russia.-)

Of course what happened in the past was not their fault but this tragedy determined the faith of the whole nation for 80 years and it is very significant even now.

If this all did not happend Czechoslovakia would be economically and socially at least as strong as Germany, France or Switzerland. And it is little funny that these days, people from Germany, France or Britain consider us as being "that poor country" somewhere in the east....but you made us becoming such a country guys...or at least your polititians did.

We will never forget this and I will make sure my children learn all about the Munich Betrayal very carefully

Kind regards

Adam

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks, Adam. Can't really blame you for feeling bitter -- although it was two generations ago now.

Paul W. Shafer

Dear all:

Adam's comment is very interesting indeed. The Nazi's needed the armament factories of Czechoslovakia badly. These were outside the Sudetenland near Prague. Without the Pz 38 and all of its variants, Rommel and other Army groups would have had a hard time taking on the French tanks. The Hetzer and Marder weapons later caused havoc with the British tanks and even with the USA M-3 and M-5's.

That is one reason, why I still believe that this was a Franco-Anglo crisis. The other reason is, France and England lost all credibility with USSR after this occured which lead to the August 1939 agreement between Hitler and Stalin which really allowed for control of Europe until the Nazi defeat at Stalingrad and in Tunisia/Sicily.

Paul Shafer

Brett Holman

Post authorThat's all true, but France and Britain both put the year gained at Czechoslovakia's expense to good use as well, particularly in the air. The Soviet alliance counterfactual is hard to evaluate; I don't think anybody rated the Red Army much in the wake of the purges, and they'd have had to force their way through Poland to get to Czechoslovakia. Soviet air support would have arrived much quicker, but I wonder how much it could contribute, so far from its own supply organisation.

Paul W. Shafer

Brett:

It is documented that the French and British considered the Soviet army and air force to be inferior in 1938 and probably would have had a difficult time moving through Poland (Moldovia?) to do much. However, the simultaneous threat of France (with some BEF) moving from the West and USSR moving from the East may have prevented Hitler from moving beyond the Sudetenland so fast and delayed the invasion of Poland by the Nazi's and USSR. The threat of using the early British heavy longer range bombers may have helped as well.

Britain did gain an additional year and one half to bring more Hurricanes, Blenheims and early heavies on line. They were extremely smart awarding a contract to Supermarine for the Spitfire and getting them built during this year and one half. They were able to fully mechanize their army, albeit the BEF was too small. However, they were very short on adequate armor, anti-tank and AA units.

In the one year gained, France did a little to improve their armored forces, but not enough of the tanks that mattered: Somua's, Char B-1's and the advanced Renault tank. They did not build enough mechanized artillery or adequate anti-tank units. France also did not listen to de Gaulle and other French and British armor experts to develop independant armored divisions until 1940. France also did little to improve their fighter force. They chose to continue to build the obsolete MS-406 in lieu of the D-520 and D-550. They chose not to buy and use the Merlin I engine. They did not manufacture enough LeO bombers instead choosing Berguet's which and did not purchase USA planes (Douglas bomber and dive bombers) until the last minute. France was extremely short on AA and mechanized infantry. France chose to work on the Maginot Line but did not complete it to Lille.

During this one year, the Nazi's more than doubled their armored units and mechanized units as well as increasing their bomber forces. A large part of this was from Czech armament factories.

Brett Holman

Post authorBut as we know (and the British and French staffs knew), the threat of attacking Germany from the West was just a threat. The French were no more capable of invasion in 1938 than they were in 1939; if the RAF had tried to bomb Germany with any intensity, it would have been trounced as thoroughly as it was with the Kiel raids (although that does depend on the state of the Luftwaffe's north sea defences, which may have been weaker in 1938 than they were in 1939). That was the reality; the illusion was even worse, since the Allies thought Germany was stronger than it was (at least in the air). And as the Chain Home system wasn't started until January 1939, Britain felt very vulnerable to a knock-out blow. I think this is a case where hindsight is 20/20.

Paul W. Shafer

After being wined and dined by Goering and visiting the German aircraft factories and even the jet engine plant as it was, the chief of the French Air Force Joseph Vuillemin reported back to Gamelin and the French government, "if the French Air Force went to war in 1938, it would be wiped out in less than two weeks." This was in early August 1938.