Michael Kerrigan. World War II Plans That Never Happened. London: Amber Books, 2011. That strange zone between what might have been and what was. Looks at various operational plans considered at some stage by one side or the other, usually getting as far as getting a codename -- from Operation Stratford to Operation Downfall. Review copy.

The Emperor’s Viceroy

In 1935, the Emperor of Abyssinia, Haile Selassie, tried to buy the Airspeed Viceroy, an aeroplane which had been built to order for the London-Melbourne air race the year before. The Viceroy (above) was a one-off, customised version of Airspeed's successful Envoy, a twin-engined civil transport which could carry six passengers in addition to its pilot. Improvements included more powerful engines, an auxiliary fuel tank and a higher take-off weight. But it failed to complete the air race, pulling out at Athens due to mechanical troubles. Still, it would have made a nice plaything for an emperor, you might think; but that's not why he wanted it. He wanted it for a bomber.

Nevil Shute, then managing director of Airspeed, tells the story in his autobiography, Slide Rule. In autumn 1935 he was approached by 'Jack Norman' (a pseudonym chosen by Shute) wishing to purchase the Viceroy on behalf of a client, Yellow Flame Distributors, Ltd, 'whose business was the rapid transport of cinema films between the various capital cities of Europe'.1 As the Viceroy had just been sitting in a hangar for months after being recovered from its former owner (who had refused to pay for it and indeed sued Airspeed for their troubles), Shute was very glad to shift it and so set his men to work getting it ready for flight. But then Norman came back and told Shute that Yellow Flame were worried about the inflammable nature of celluloid and asked, 'Could we fit bomb racks underneath the wings to carry to films on?'

...continue reading

- Nevil Shute, Slide Rule: The Autobiography of an Engineer (London: Vintage Books, 2009 [1954], 212. [↩]

A myth of the Blitz?

I'm giving a talk at the XXII Biennial Conference of the Australasian Association for European History, being held in Perth this July. It's a big conference with some big names (e.g. Omer Bartov, Richard Bosworth, John MacKenzie), and there's an appropriately big theme: 'War and Peace, Barbarism and Civilisation in Modern Europe and its Empires'. My talk will be about the reprisals debate in Britain during the Blitz. Here's the original title and abstract:

'Bomb back and bomb hard': A myth of the Blitz

In Britain, popular memory of the Blitz celebrates civilian resistance to the German bombing of London and other cities, emphasising positive values such as stoicism, humour and mutual aid. This 'Blitz spirit' is still called to mind during times of national crisis, for example in response to the July 2005 terrorist bombings in London.

But the memory of such passive and defensive traits obscures the degree to which British civilian morale in 1940 and 1941 depended on the belief that if Britain had to 'take it', then Germany was taking it as hard or even harder. As the Blitz mounted in intensity, Home Intelligence reports and newspaper letter columns featured calls for heavier reprisals against German cities. Propaganda, official and unofficial, responded by skirting a fine distinction between reporting the supposedly heavy bombardment of strictly military targets in urban areas and gloating over the imagined suffering of German civilians. That the RAF's bombing efforts over Germany at this time were in fact wildly inaccurate and largely ineffective is beside the point: nobody in Britain was aware of this yet.

In this paper I will try to restore a sense of these forgotten aspects of the 'Blitz spirit', and attempt to locate their origins in pre-war attitudes to police bombing in British colonies and mandates, and in reactions the predicted knock-out blow from the air which dominated popular perceptions of the next war in the 1920s and 1930s.

A more recent and abbreviated version:

'Bomb back and bomb hard': the reprisals debate during the Blitz

It is often argued that there was little enthusiasm in Britain for reprisals against German cities in retaliation for the Blitz, unlike the First World War. There was in fact a serious contemporary debate about whether enemy civilians could or should be targets of bombing, which I will show derived from the prewar and wartime public understanding of the potential and proper use of airpower.

As these perhaps show, my thinking on the reprisals question is changing a bit, which is not surprising since I'm still researching it. What I plan to do over the next few weeks is to do some of my thinking out loud by way of blogging -- appropriately, since I became interested in this topic while post-blogging the Blitz. So watch this space!

Death on the Euphrates

Military History Carnival #27 is now up at Cliopatria. One of the posts featured is from Zenobia: Empress of the East and concerns a recent scholarly suggestion (made by Simon James, an archaeologist) that in the 3rd century CE, Sassanid soldiers used chemical weapons against Dura-Europos, a Roman fortress city on the Euphrates. As a weapon, gas is associated with the First World War so strongly now that it's always surprising to think of it being used before then (or at least considered: I've long been meaning to write a post on Thomas Cochrane, Lord Dundonald, and his chemical warfare proposals in the Napoleonic and Crimean wars). The post at Zenobia is quite detailed, so I won't recap the argument here; instead I'll confine myself to a couple of remarks.

Firstly, the gas in question is sulfur dioxide, described as 'a poisonous gas, that turns to acid in the lungs when inhaled'. I'm not a chemist or a medical doctor, but while sulfur dioxide is no doubt highly unpleasant, it's not particularly dangerous. It would now be classed as an irritant or lachrimator (i.e. tear gas). I don't think it's ever been used as a weapon in modern times (though only because Cochrane's idea was turned down by the Admiralty). Secondly, one of the criticisms of Jones's idea made at Zenobia is that there is no written record of this stratagem being used at Dura-Europos or anywhere else, either by the Sassanids or the Romans. That's the sort of problem historians always have with archaeology, though; and it's precisely because the written record is so patchy that archaeology is necessary. The way gas was used at Dura-Europos, if it was used at all, meant that it could only be used in a very limited number of tactical situations and so might not have been used very often, or have interested contemporary writers. It's still probably doubtful that anything of the sort happened, but it's certainly intriguing to ponder.

Debating bombing and foreign intervention — IV

Time to put this increasingly misnamed trilogy out of its misery. (It's been going so long I can't remember why I started it!)

To reprise: on 21 June 1938, Philip Noel-Baker initiated a debate in the House of Commons about how Britain should respond to the increasingly-common (and, he asserted, illegal) bombing of civilian targets in warfare, as evidenced by China and Spain. He made a particular point of discussing Nationalist attacks on British-flagged merchant vessels in Spanish waters. The Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, responded, giving his own view of what sort of bombing was permitted by international law, and essentially saying that it was impossible in practice to do anything to defend these ships. A number of MPs rose to speak following the PM, largely on party lines. Here are the rest of them.

...continue reading

Post-blogging 1940: final thoughts and conclusions

I've now finished my (somewhat piecemeal) post-blogging of the Blitz. It's time to step back and see if there is anything to made of the whole thing.

I'll start with the things I wish I'd done differently. I had intended to use a greater diversity of sources, especially the Popular Newspapers during World War II microfilm collection, which includes the Daily Express and the Daily Mirror along with some Sunday papers. I only managed to do this for the period around the bombing of Coventry. You can see from there that these papers were much more visceral, shall we say, in their reactions to German air raids than the more staid Times, Manchester Guardian or even the Daily Mail. My coverage of the Mail anyway ends after early October so that meant much of the last few rounds of post-blogging relied on the old standbys of The Times and the Guardian, and was less interesting because of it. (Though fewer sources did make them easier to write, not unimportant given I was trying to get each day's post up before midnight!) The exception was for the Clydeside blitz, where I used only a single source, the Glasgow Herald. My aim there was to try and see how the local press covered its own blitz, rather than just taking in the usual views from London (or Manchester). But I think it might have been more valuable had I contrasted the Herald's coverage with, say, The Times, to see if there were differences or whether they in fact were similar (whether because of censorship, the pressure of events or conformity to now-established stereotypes of how blitzes went).

...continue reading

Acquisitions

Brian Farrell and Sandy Hunter, eds. A Great Betrayal? The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2010. A diverse collection of articles: strategy, historiography, oral history, operational history. Of particular interest is a contribution by John Ferris on British perceptions of Japanese airpower (includes Darth Vader bonus quote).

A. L. Goodhart. What Acts of War are Justifiable? Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940. In particular, justifiable against civilians (such as bombing, reprisals). No. 42 in the Oxford Pamphlets on World Affairs series.

Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt. The Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference Book 1939-1945. Hersham: Midland Publishing, 2011 [1985]. A classic (and weighty!) reference listing nearly all Bomber Command missions, targets, results, losses, etc, which I have wanted for some time.

Peter Monteath. P.O.W.: Australian Prisoners of War in Hitler's Reich. Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia, 2011. I already own a book called POWbut that is about Allied POWs in general. I probably should read it before I read this one though!

Wednesday, 21 May 1941

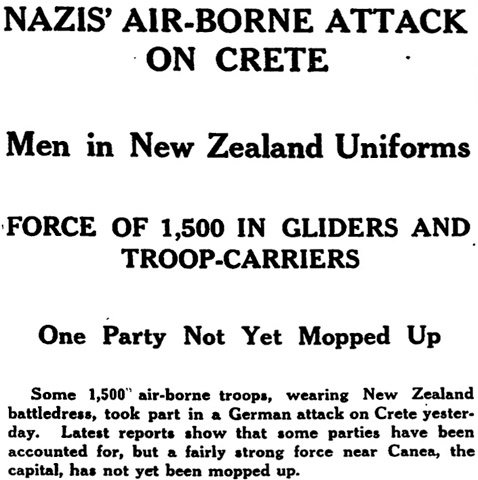

Hitler is on the move again! Yesterday, German airborne forces attacked Crete. According to the Manchester Guardian (5), Churchill informed the House of Commons of this news last evening, but his information was dated 3pm. However, 'at noon the situation was reported to be in hand'.

The attack began early in the morning with intense bombardment of Suda Bay, where there is anchorage for the largest vessels, and on aerodromes in the neighbourhood. The parachute troops, brought in troop-carriers and gliders, began to land, apparently with the object of capturing Maleme, an aerodrome on the Bay of Canea. In this they have so far failed. A military hospital which was seized was retaken by our troops under General Freyberg. From time to time the Germans bombed and machine-gunned anti-aircraft defences. Heraklion (Candia) was bombed, but no landings have so far been reported there.

The size of Allied forces on Crete is unknown, but two weeks ago it was reported that two Greek divisions had arrived there following the German conquest of the mainland, and there are also British and New Zealand forces present. King George of the Hellenes and members of the Greek government also managed to evacuate to the island.

...continue reading

Tuesday, 20 May 1941

For the first time in a while, The Times and the Manchester Guardian differ in their lead stories. The latter (above, 5) focuses mainly on the surrender of seven thousand Italian soldiers in northern Abyssinia, but also notes a repulse of German armoured columns near Sollum and a new RAF attack on Vichy aerodromes in Syria. The Times deals only with Syria. There's surprisingly little crowing in either paper about this victory; perhaps because Gondar and Gimma are still holding out, or perhaps because, as a leading article in the Guardian says, 'As a nation [...] we are more disturbed by our defeats than excited by our victories' (4). But the The Times does rub salt into Italian wounds with a little article which points out that while it took the Italians 'seven months to march 425 miles' in their conquest of Abyssinia in 1935-6, 'Imperial Forces have covered a distance of 1,500 miles in 94 days' in order to free it (3).

...continue reading

Monday, 19 May 1941

There is a lot going on in the Mediterranean and African theatres at the moment. The big news, as reported here by The Times, is that Italian forces in northern Abyssinia have asked for surrender terms (4). They, along with the Duke of Aosta, Viceroy of Abyssinia, are holed up in 'the mountain stronghold of Amba Alagi', where they are being battered by Indian and South African troops. According to the delayed dispatch of The Times's correspondent, Italian morale was very low nearly a week ago, and must be on the verge on breaking by now:

It is a strange twist of fortune that has made the caves where Haile Selassie once sheltered the refuge of the Duke of Aosta's Army. Its disintegration goes on constantly. Deserters at night time steal their own lorries to make a getaway. Many reach the security of our lines. Some are not so lucky.

Once Amba Alagi falls, there will be only two remaining centres of Italian resistance left in Abyssinia.

...continue reading