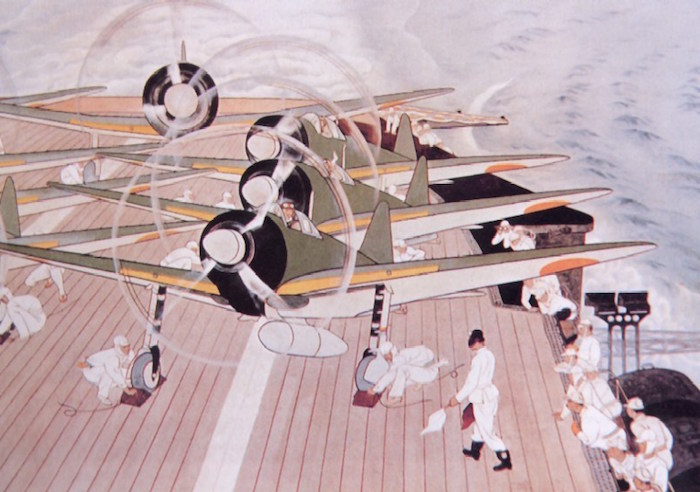

Preparing for take-off

Apropos of nothing, here’s a (somewhat cropped) c. 1943 painting by a Japanese artist named Shori Arai. (Sometimes called Maintenance Work aboard Aircraft Carrier II, though clearly it’s not maintenance that’s going on there.) The original is held by the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. It was also issued as a postcard by the […]