Mirrors and lenses

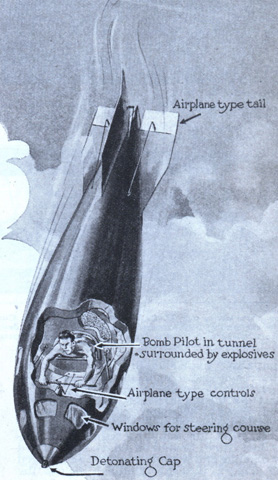

Via Modern Mechanix comes this supposed Japanese suicide bomb. It’s from the April 1933 issue of Modern Mechanix, an American magazine. It’s not an aeroplane but a precision guided munition, with the guidance supplied by the pilot inside the bomb itself. The accompanying article claims that Japan was using such bombs in China. Now, this […]