Publication: ‘Constructing the enemy within’

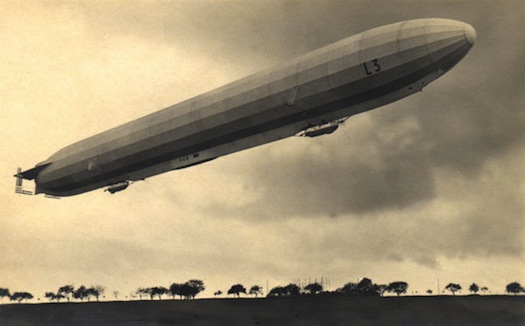

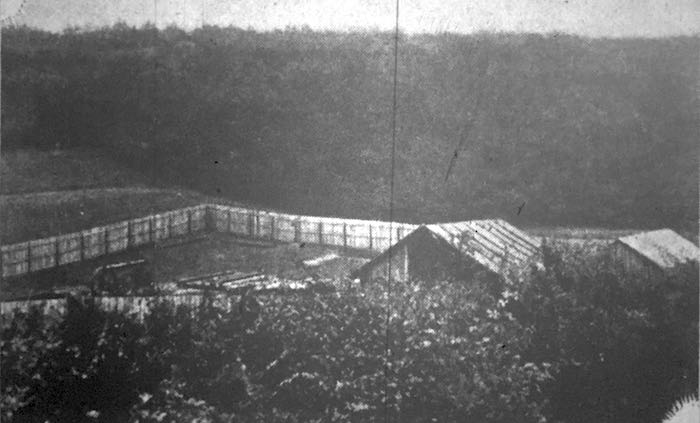

The latest issue of the British Journal for Military History is out, and with it my peer-reviewed article ‘Constructing the enemy within: rumours of secret gun platforms and Zeppelin bases in Britain, August-October 1914’: This article explores the false rumours of secret German gun platforms and Zeppelin bases which swept Britain in the early months […]