Self-archive: ‘Spectre and spectacle’

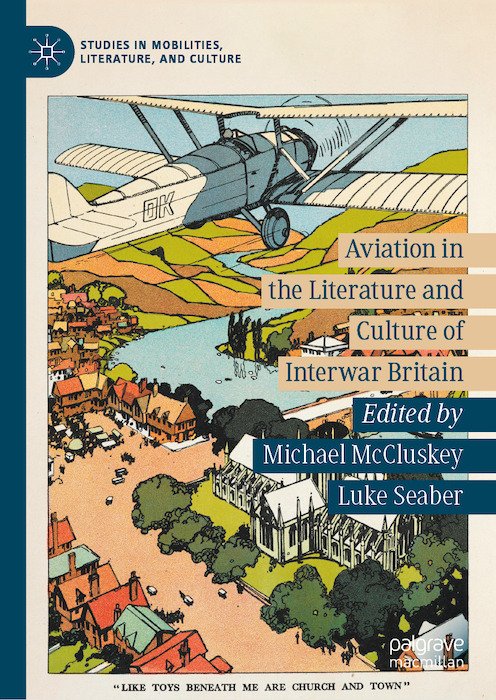

After thirty-six (!) months, ‘Spectre and spectacle: mock air raids as aerial theatre in interwar Britain’, my chapter in Michael McCluskey and Luke Seaber, eds., Aviation in the Literature and Culture of Interwar Britain, is now available for a free download under green open access (in this case, pre-copy editing). Here’s the abstract: You can […]