Monday, 19 September 1938

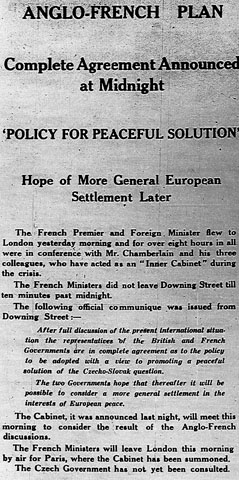

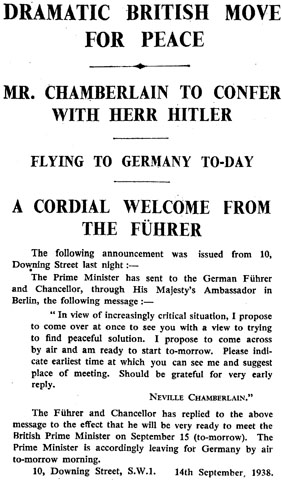

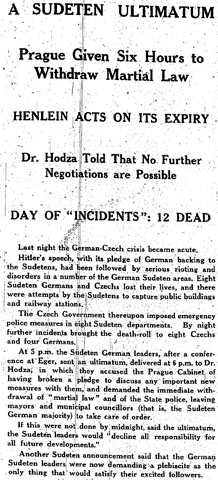

Another week of crisis begins. How much longer can this go on? The most significant news from the weekend concerns another round of shuttle diplomacy — this time it’s the French Premier, Édouard Daladier, and Foreign Minister, Georges Bonnet, who have flown to London to consult with their British counterparts. The official communique, which can […]