Australia and the airship — IV

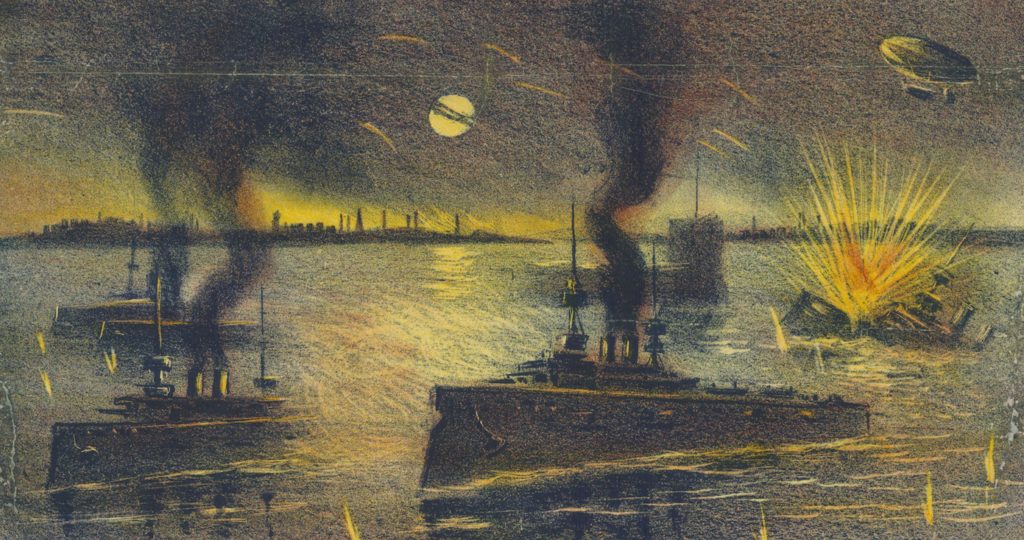

The previous post in this series was supposed to be the last. But in the course of taking two months to write it, I managed to forget about another, earlier association between a White Australia and an Australian airship. This one wasn’t a real airship; it was a fictional one which appeared in Randolph Bedford’s […]