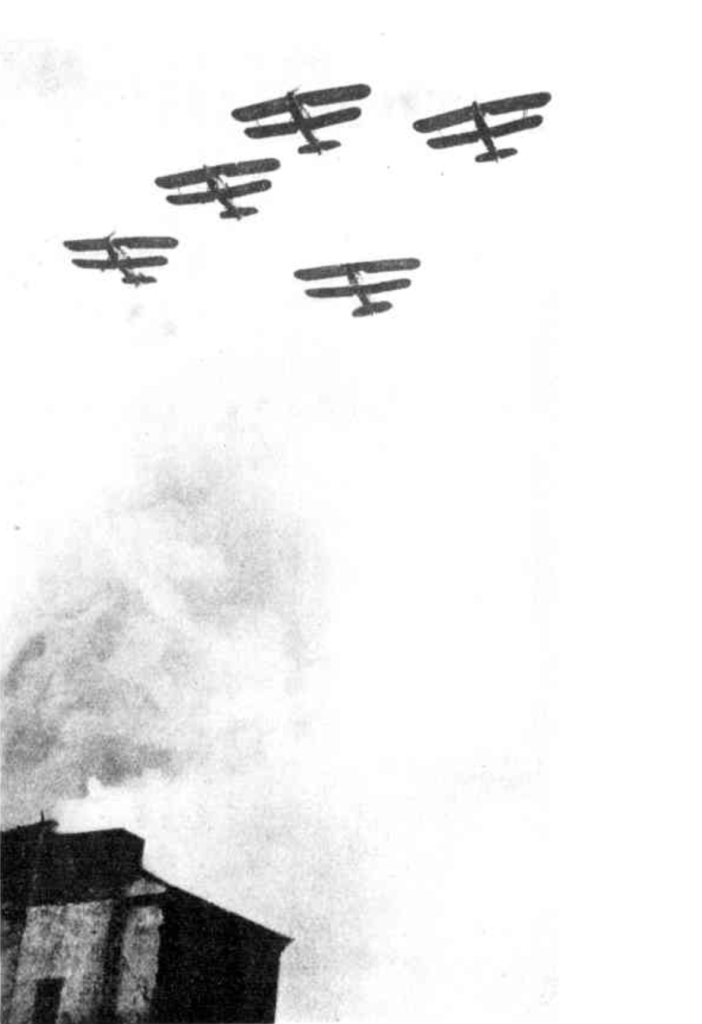

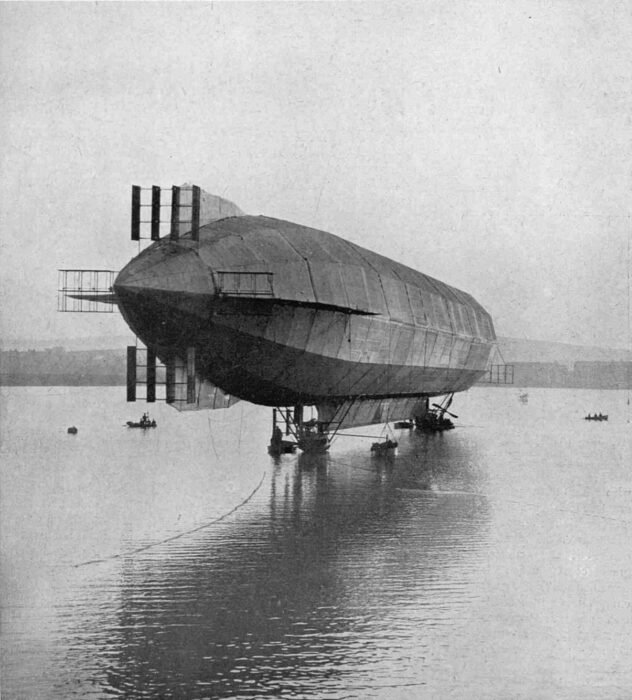

Civil defence, British pluck, and the Gotha shock

[Edited version of an oral summary of ‘Mutual aid in an air-raid? Community civil defence in Britain, 1914-18’, International Society for First World War Studies Virtual Conference 2021: Technology, online, 16-18 September 2021.] The first thing to note is that the German air raids on Britain of the First World War were much smaller in […]