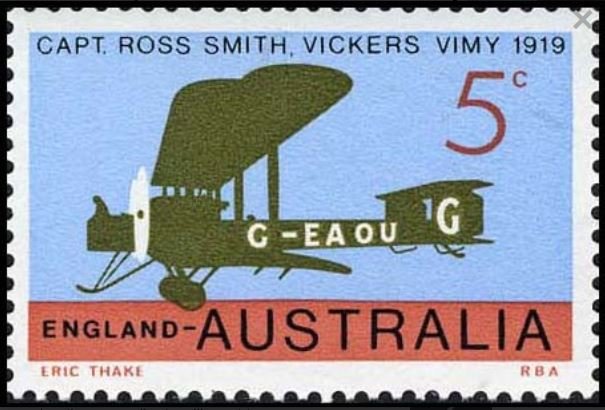

Alien airmen and will-o’-the-wisp bridges

Although the war had been over for more than a year by this point, in 1920 the editor of Sea, Land and Air issued a rather hysterical warning of the danger of foreign pilots being allowed to fly in Australia.1 The passenger-‘plane of to-day may be the bomber of to-morrow. It depends on the man […]