The Imperial Aircraft Flotilla — I

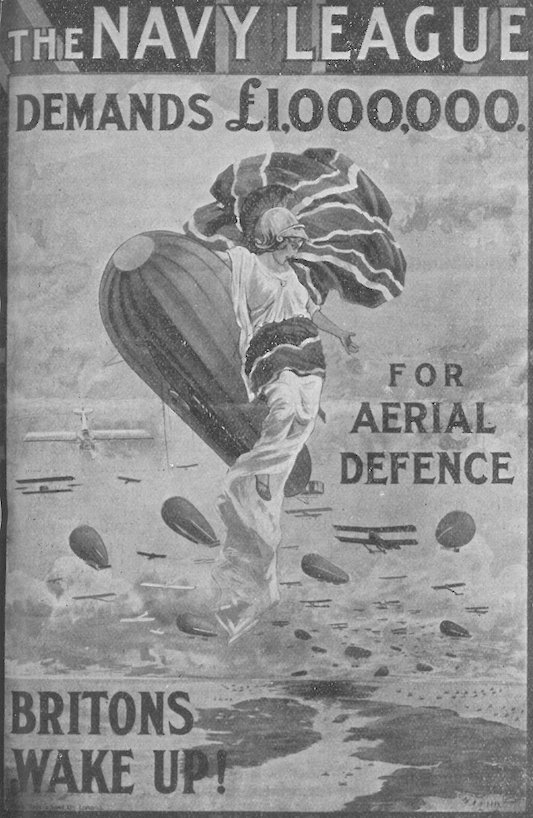

We are familiar enough with the Spitfire Funds of the Second World War, in which patriotic individuals and groups could buy aircraft for the nation. There was a fair amount of precedent for this. In the early 1930s, Lady Houston more than once offered the government hundreds of thousands of pounds for air defence, though […]