Faster, higher, stronger

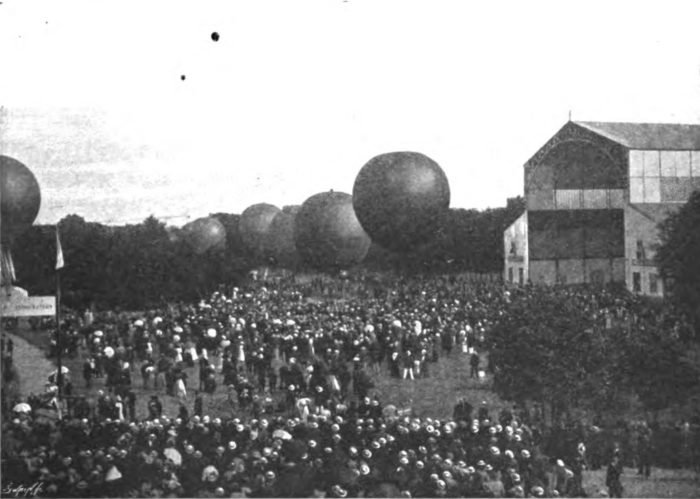

It is sometimes1 claimed that ballooning was an event at the 1900 Paris Olympics. I don’t think it can have been. But it’s genuinely a bit murky, because this was only the second modern Olympics and the planning process evidently was not as formalised as it later became. The Olympics were held that year as […]