Thursday, 15 May 1941

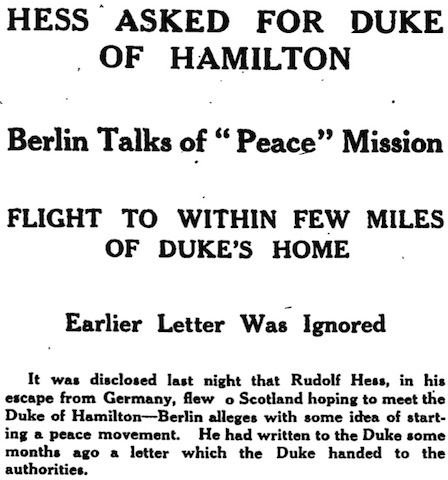

The remarkable flight to Scotland of Rudolf Hess still dominates the headlines today, though much more so in the Manchester Guardian (5) than in The Times, it must be said. More details are emerging. It now seems that Hess was trying to meet with one specific person, the Duke of Hamilton, whose seat is at […]