Abstract: AAEH 2015

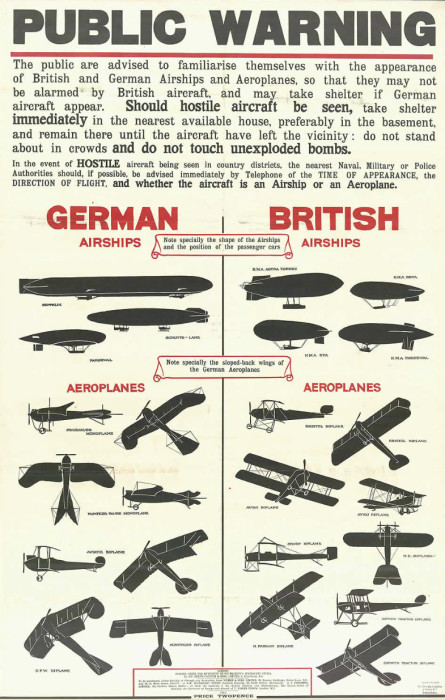

The Australasian Association for European History is, by widespread acclaim, the best conference series ever, and so I’m pleased to report that I will be speaking at the next one, to be held in July at the University of Newcastle. The title of my talk is ‘Zeppelinitis: constructing the German aerial threat to Britain, 1912-16’, […]