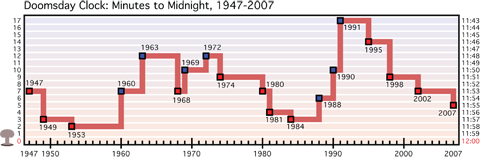

Five to

[Cross-posted at Revise and Dissent.] [Image removed at the request of the copyright holder.] The minute hand of the famous Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has just moved closer to apocalypse: it is now set at five minutes to midnight. This is the most dangerous level it has been since 1988. […]