A shelter of one’s own — I

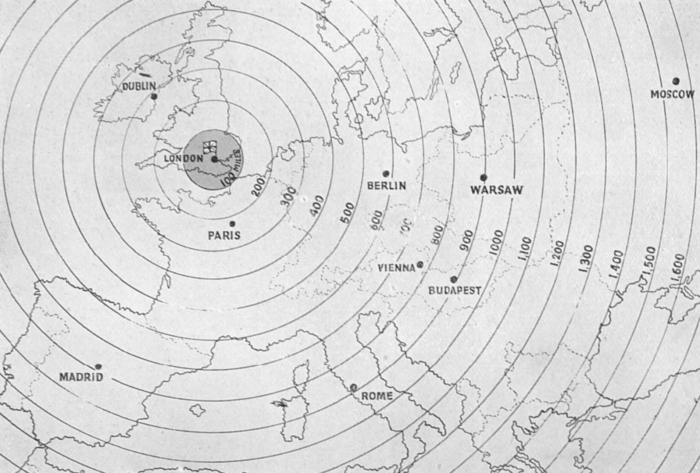

Recently, Alexandra Churchill tweeted a photo of an air raid shelter in London in 1917: She’s absolutely right, and I’ll eventually come back to this, sort of; but Rob Langham made a slightly different point which I want to follow up first: That’s an incredible photo for many reasons. @IanCastleRaids @ZeppRaider and @StowAero will likely […]