Thursday, 20 May 1909

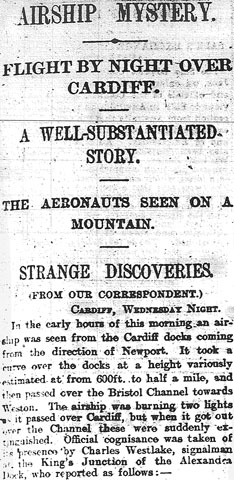

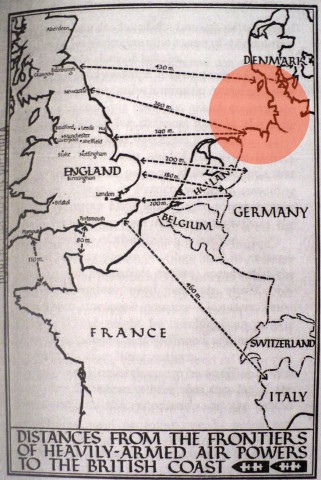

The Globe has a slew of new reports from last night (p. 7), from Norwich, Wroxham, Sprowston, Catton and Tesburgh in East Anglia, Pontypool in Wales (by workers at a forge, an architect and two postal workers), and Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) in Ireland. Some saw searchlights, some heard a ‘whizzing’ sound, some saw a […]