Breaking the tyranny of distance

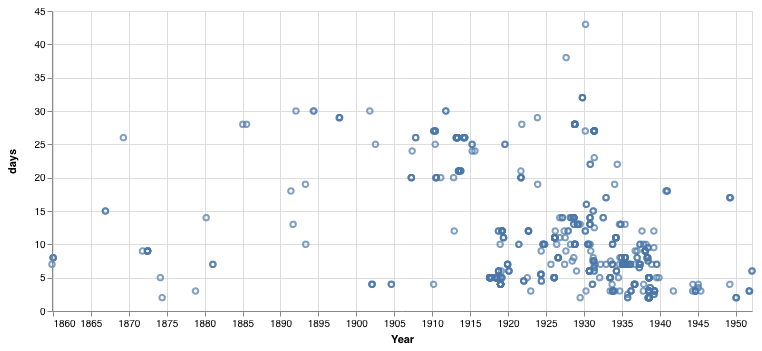

[Cross-posted at Airplay.] Australia is a long way from anywhere, even from itself. It nearly always takes a long time to get to where you want to go. Historian Geoffrey Blainey famously popularised the idea that this remoteness has shaped Australian history and culture in the title of his 1966 book, The Tyranny of Distance. […]