Secret Zeppelin bases in Britain — I

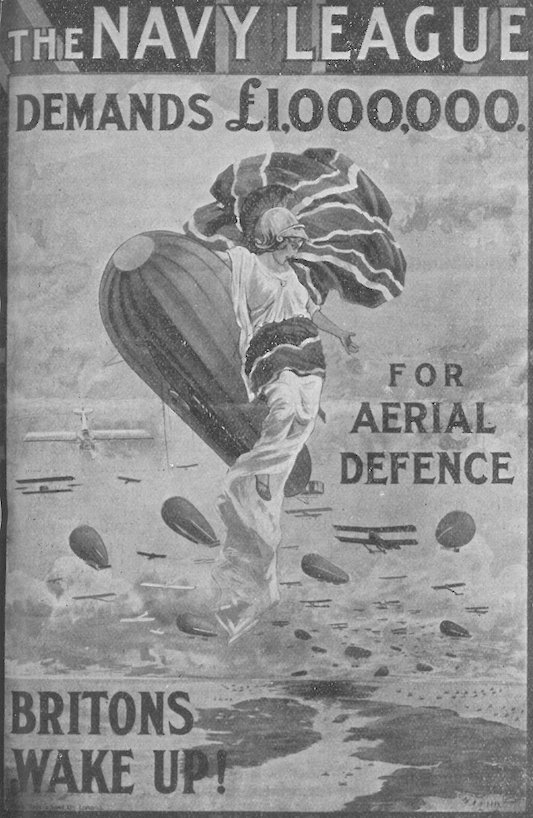

On ABC New England last week I briefly mentioned rumours of secret Zeppelin bases in Britain in the early months of the First World War. So far as I have been able to determine, the stories, which peaked in October 1914, centred on three locations: the Lake District, the Scottish Highlands and the Chiltern Hills. […]