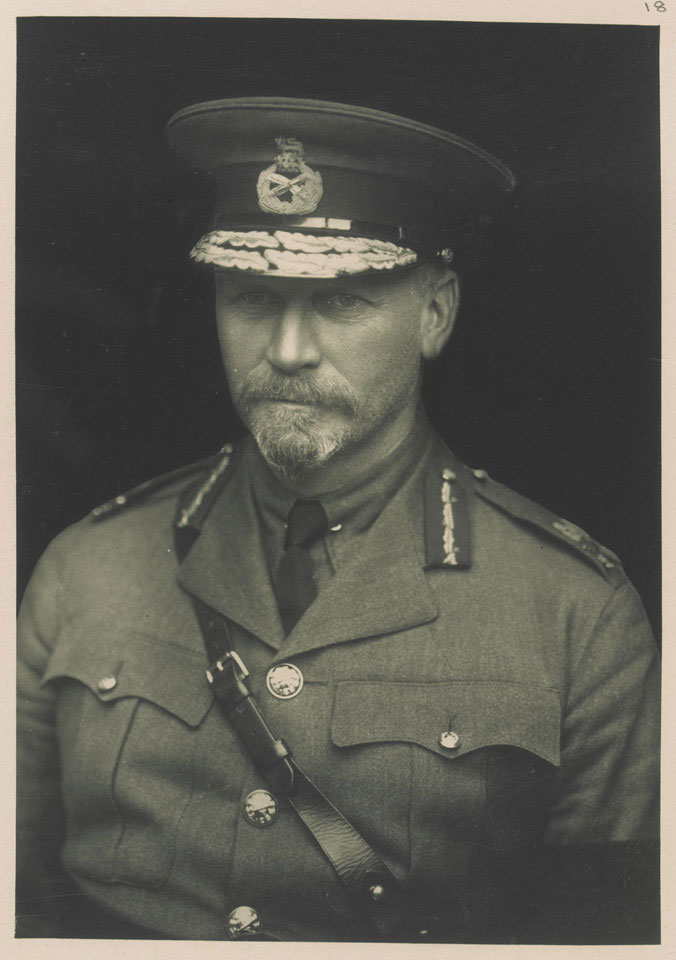

Jan Smuts, zeroth air minister?

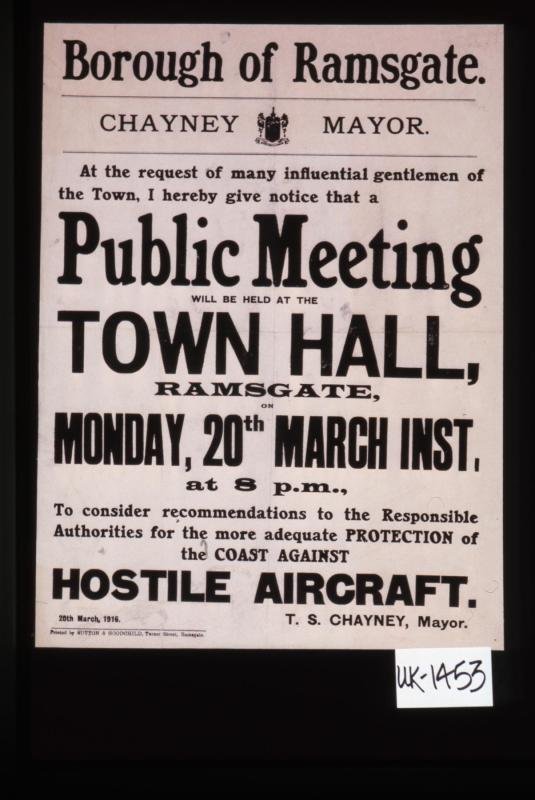

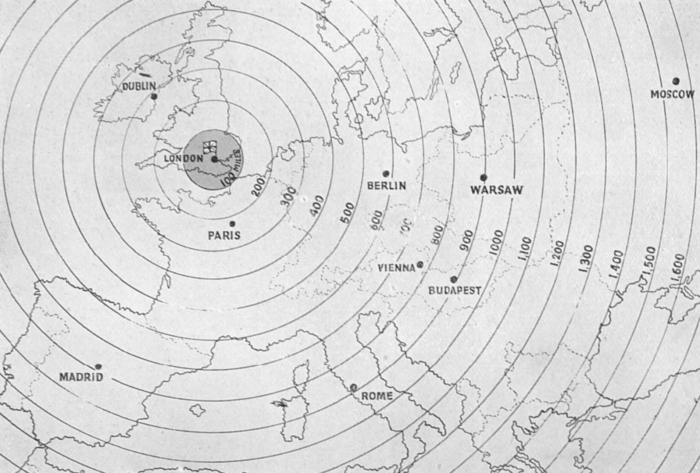

Like many people – out of the sort of people who know these sorts of things, that is – I knew of Jan Smuts’ key role in the origins of both the RAF and the Air Ministry. It was the so-called ‘Smuts report‘ to the War Cabinet, in August 1917, which set the whole process […]