In case you were wondering

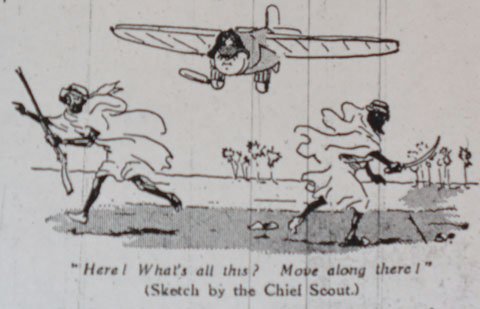

A couple of recent tweets from @zunguzungu (Aaron Bady): I had to include this disclaimer: “The Scout Association does not endorse Mr. Bady’s article or the use of air power against civilians” in my upcoming article. It’s a marvelous sentence. It is indeed. But what would B-P think?