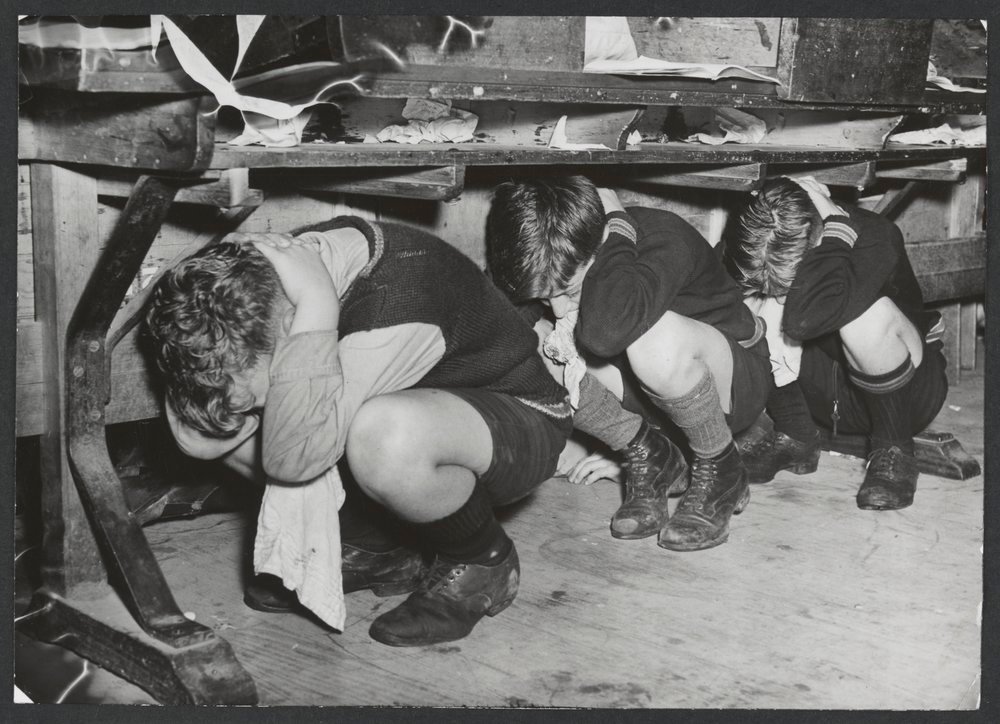

If war should come, pump up the volume

Dr Beachcombing of Beachcombing’s Bizarre History Blog kindly dropped me a line to alert me to his post about Public Service Broadcasting, a British music duo who draw on old propaganda and information films for inspiration and samples. A number of these are from the Second World War period, including ‘Spitfire’, ‘London Can Take It’, […]