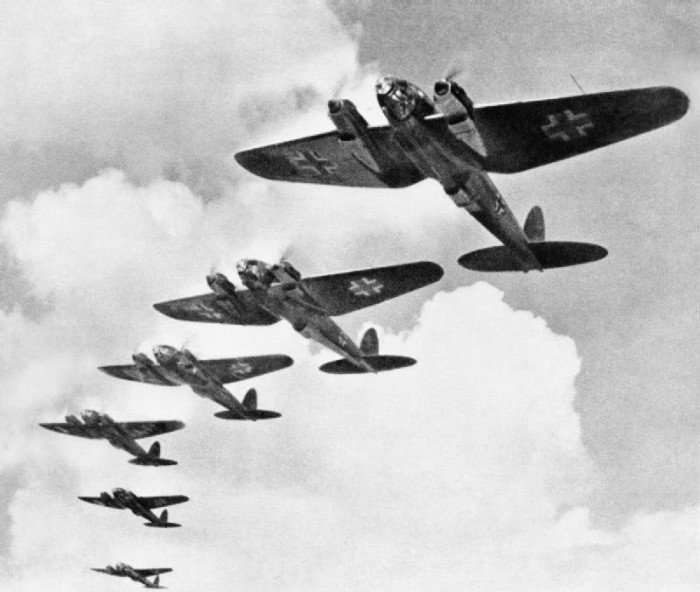

The first bombing war

In the last decade or so, it seems to have become a thing to refer to the German air raids on Britain during the First World War as the ‘First Blitz’. There are now at least three books on the topic with that title or variations thereof: Andrew Hyde’s The First Blitz: The German Bomber […]