Downward, inward persuasion — III

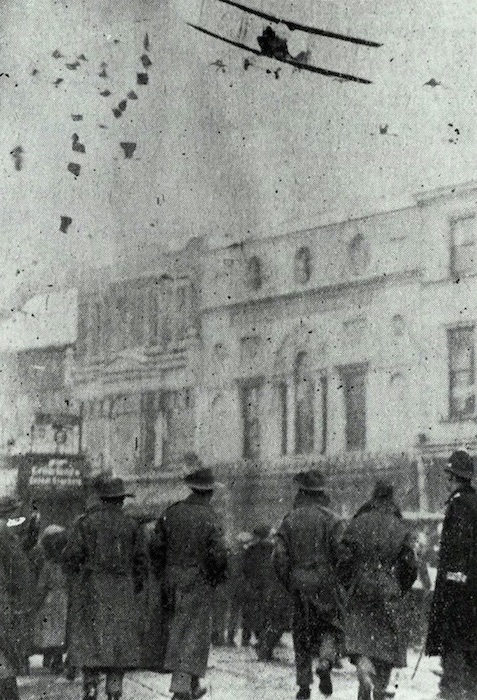

In my previous post I looked at who was behind the leaflet drop drop on striking workers at Coventry in December 1917. The official answer was that it was an obscure MP and military administrator, Major H. K. Newton; I suggested that it was actually an RAF officer and Ministry of Munitions propagandist, Captain Ernest […]