The canals of Mars, 1861-1970 — II

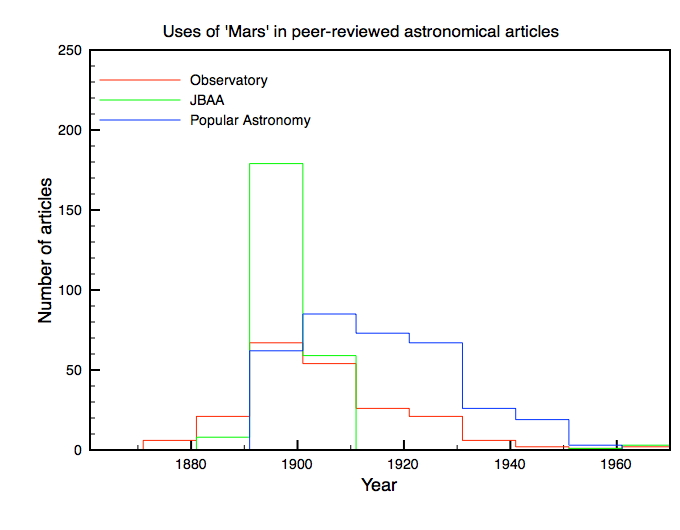

In my post about the lingering scientific interest in the Martian canals hypothesis after 1909, I said that there was a problem with journal coverage. What do I mean by this? Have a look: This is a repeat of the first plot in the previous post, showing the number of articles published in peer-reviewed astronomical […]