After Millennium — I

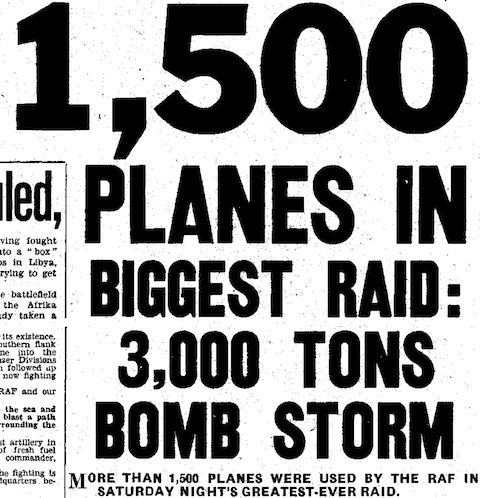

Operation Millennium was the RAF’s first ‘thousand bomber raid’, on Cologne on the night of 30 May 1942. By making a maximum effort and by using aircraft and aircrews from training units (since the Admiralty did not consent to the diversion of Coastal Command aircraft), Air Vice-Marshal Harris was able to scrounge a total of […]