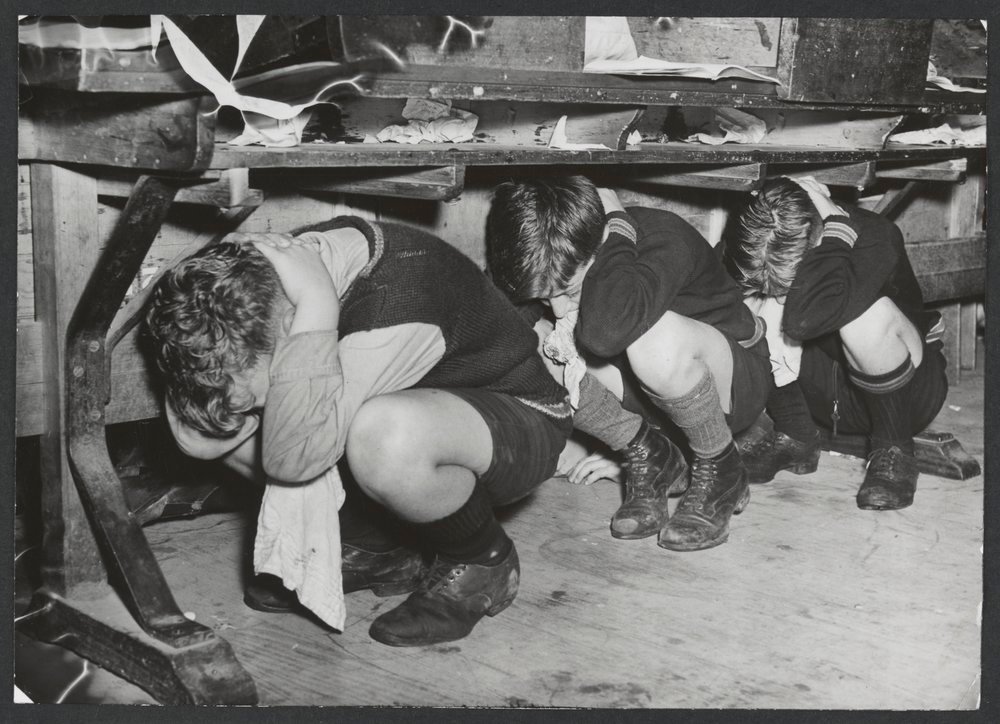

Duck and cover, 1942

This is an image we might particularly associate with the United States in the 1950s, when schoolchildren were taught to duck and cover in the event of the flash of an atomic blast. But its use in civil defence drills predates the Cold War (albeit without a Bert the Turtle to help kids remember the […]